The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #46 - #54

Quick Find: #46, #47, #48, #49, #50, #51, #52, #53, #54

#46 Adjustable Dado and Plow Plane, 10 1/2"L, various widths, 5 3/4lbs, 1874-1942.

This

plane was designed by Justus

A. Traut, a German immigrant, who was generally known as

"The Patent King

of the United States." He held at least 145 patents, ranging

from

woodworking tools to bottle openers. He held the basic

patent for the #45, but this,

and the following plane, the #47, are commonly known as

"Traut's Patent

Combination Plane".

This

plane was designed by Justus

A. Traut, a German immigrant, who was generally known as

"The Patent King

of the United States." He held at least 145 patents, ranging

from

woodworking tools to bottle openers. He held the basic

patent for the #45, but this,

and the following plane, the #47, are commonly known as

"Traut's Patent

Combination Plane".

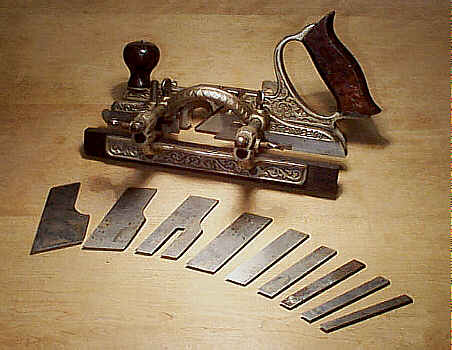

This is yet another in a series of combination planes

offered by Stanley.

The distinguishing characteristics of this plane is that it

has fewer cutters,

all of which are ground straight across, and that they are

skewed, which makes

the plane more versatile when used across or against the

grain. Most of the

planes are found missing all but one of their cutters, with

the only one

present being the one left in the plane from the last time

it was used. Cutters

from the other combination planes will not work in this one

as the edges of the

#46's cutters are

beveled (relative to

the cutter face). If you need cutters, you often will pay

more for a complete

set than you did for the plane itself.

Like the #45, this plane originally was cast with floral

motifs on its main stock,

sliding section, and fence. Prior to the addition of its #45-like fence,

which was introduced ca. 1900, the sliding section doubled

as the fence when

the plane was used for ploughing and rabbeting. A

detachable guard plate, which

is often missing from the plane, was screwed to the

sliding section's skate for

this function. The guard plate extends the depth of the

sliding section so that

it can reference the edge of the stock and position the

cutter at a constant

distance from the edge. If you note two holes in the

sliding section, and

there's nothing filling them, your plane had a detachable

guard plate, which

long ago became detached from your plane. A lot of guys

are looking for guard

plates, and the screws that hold them to the plane (they

are rather fragile),

so you'll have plenty of shoulders to cry on while hunting

for yours. Do be

sure that you're after the proper guard plate as there is

a very subtle

difference between them where the earlier ones have small

thumb screws to

fasten the guard plate to the sliding section and the

later ones have slotted

screws to accomplish the same. Test that your guard

plate's inner face is flush

with the inner face of the sliding section, when the guard

plate is attached.

Another commonly

missing

part is the wrap around depth stop, which came with the

earlier models of the

plane. This fence, made of cast iron, straddles the main

stock and fits over

the top of the regular depth stop. This stop is superflous,

and many guys just

tossed them, using just the regular depth stop instead. This

wrap around depth

stop is probably the hardest part to find for this tool. And

while on missing

parts, it should be noted that this plane only came with a

single depth stop

(unlike the #45) and that only one thumb screw was supplied to

secure the depth stop;

there are two positions for the depth stop and it and its

screw are swapped to

the desired location.

Another commonly

missing

part is the wrap around depth stop, which came with the

earlier models of the

plane. This fence, made of cast iron, straddles the main

stock and fits over

the top of the regular depth stop. This stop is superflous,

and many guys just

tossed them, using just the regular depth stop instead. This

wrap around depth

stop is probably the hardest part to find for this tool. And

while on missing

parts, it should be noted that this plane only came with a

single depth stop

(unlike the #45) and that only one thumb screw was supplied to

secure the depth stop;

there are two positions for the depth stop and it and its

screw are swapped to

the desired location.

After the guard plate was dropped for the fence

proper, the plane pretty

much followed the #45 in its evolution - the plane

dropped the japanning

in favor of the flashy nickel plating ca. mid 1890's, a

rosewood strip was

added to the fence ca. 1905, the rosewood handle style

changed over time,

etc... One notable difference is that the rosewood front

knob always remained

on the main stock, and was not repositioned onto the fence

as in the case of

the #45. Also, the floral casting was continued on the #46 until its production was KO'ed

permanently during

the big war.

When the guard plate is removed from the plane, which

is what's done when

cutting dados, a batten must be used to track the plane. The

batten is tacked

along the right side of the dado's position on the wood so

that the right side

of the plane has a consistant reference to cut the dado. The

depth stop is

positioned on the sliding section, which is opposite when

grooving or rabbeting

where the depth stop is positioned on the main stock. The

spurs - one on the

sliding section and one on the main stock - are lowered so

that they can score

the wood prior to the cutter doing its cutter thing. The

spurs are arranged so that

their bevels face each each other. It's surprising how many

planes can be found

with the spurs turned around with the bevels facing outward

from the cutter.

Speaking of spurs, many of the planes are missing theirs.

Like the guard plate,

there are two basic kinds of spurs: those that are wedged

into milled slots and

those that are secured with a small screw. The latter spurs

are the easiest to

use, and they can be flipped end for end when one end of the

spur no longer has

any more life left to it.

The plane should be inspected for cracks or repairs

to the castings. The

plane is a rugged one, but like any other piece of cast

iron, it cannot

withstand body slams to concrete or the like. Check the

looping portion of the

casting about the handle, the casting on the fence where the

arms arch upward,

and the skates of the main stock and sliding section. On

this plane, and the #47, the skates are cast

integral to the plane and are not made of steel pieces

pinned the castings like

they are on the #45 and #55. You should also unscrew the

arms to make sure that

they aren't bent

This plane is a fabulous worker, much better than the

#45. The simple

act of skewing the iron makes this plane plane dados

around the #45. It also

does a fine job of cutting cross grain rabbets, a common

function when making

lipped drawer fronts. If you have money burning a hole in

your pocket, and are

given the chance to buy one, and you dig working wood with

handtools, buy this

tool! A good working example of this plane will cost less

than the number of

wooden dado planes alone that it replaces. And, unlike the

wooden dado planes,

this one won't warp on ya, which is the kiss of death for

wooden dados (warped

wooden dados will have your dados in a bind).

There is one minor nuisance that bugs me about the

plane - I find that its

arms are too long for cutting dados. The arms need to be as

long as they are so

that the tool can cut grooves over the same range that

common ploughs do.

Stanley must have recognized that the long arms bugged other

guys since they

quickly added the #47,

with its shorter arms, to their arsenal of planes. And

while on the topic of

arms, make sure that the arms are proper and not

replacements off a #45. The #46

arms measure 5" long (not counting the threaded length) on

the earlier

models, while the later models (the later production of

the nickel plated

examples) have arms of 6 1/2" long.

The following cutters come with the plane:

Cutters First Offered in 1874

|

ploughing and dadoing |

3/16", 1/4", 5/16", 3/8", 1/2", 5/8", 7/8", 1 1/4" |

|

fillister |

1 1/2" |

|

tonguing |

1/4" |

Cutter First Offered in 1884

|

slitting cutter |

V-shaped (same as that of the #45) |

Cutter First Offered in 1919

|

ploughing and dadoing |

13/16" |

Again, you'll note the presence of the mysterious

13/16" width, which

appeared simultaneously with the cutter provided for the #45 and the

introduction of the #39

13/16. The astute observer

will also note that Stanley

never offered a 3/4" cutter with the plane. Kinda makes it

tough on us

modern woodworkers, no?

#47 Adjustable Dado Plane, 10 1/2"L, various widths, 3 3/4lbs, 1876-1923. *

This plane is a funky

hybrid of the #46,

and was designed to function only as a dado plane as

evidenced by the short

4" arms that are provided with the plane. The arms are

only long enough to

accomodate the widest cutter and the sliding section. The

plane is never marked

#47, since

the #46 casting was always

supplied as the plane. In fact, the plane is embossed "No.

46".

This plane is a funky

hybrid of the #46,

and was designed to function only as a dado plane as

evidenced by the short

4" arms that are provided with the plane. The arms are

only long enough to

accomodate the widest cutter and the sliding section. The

plane is never marked

#47, since

the #46 casting was always

supplied as the plane. In fact, the plane is embossed "No.

46".

Other than the conspicuous short arms - they measure

2 1/2" long over

the unthreaded portion - there are two other distinguishing

ways to identify

the plane: 1) the front right housing for the depth stop is

ground off; 2) and

the sliding section never has holes to receive the guard

plate (remember, the

guard plate is used only for ploughing and rabbeting on the

#46). The depth stop is always

positioned in the

sliding section, to the left of the cutter, just like it

is on a wooden dado.

A fence was never supplied with the plane, nor were

there as many cutters

supplied, but both these facts are no guarantee that you

have a true #47. It

gets very confusing on the last models of this

plane, since they are identical in every way to the #46, except that they were shipped

without the fence,

have fewer cutters, and the rightmost depth stop housing

is not ground off.

These planes are always nickel plated. I'd be wary of

these later models, if

you're collecting, unless they come along with their

original box marked with a

#47 label.

I discovered a very

rare

variant of the #47,

and it's surprising

the thing was never offered this way (and on the #46, too). There is a problem with

both the planes when

using the narrowest cutter - only one spur, the rightmost

(carried on the main

casting), can be used as it's impossible to move the

sliding section close

enough to align with the cutter's leftmost edge. This is

obviously suboptimal.

On the one example I unearthed, Stanley milled an extra

recess on the left side

of the main casting for an auxilary spur thus making it

possible to remove the

spur from the sliding section and placing it in the main

casting (you can see

the extra recess in the image to the right - the recess is

directly below the

flat milled area). The narrowest cutter now has a spur

aligned with either side

of the cutter, making the plane function as it should.

Perhaps Stanley found

this milling too costly, and it seems odd that only one

example has turned up,

which suggests that maybe it was a custom order by a

smart-thinking tradesman.

I discovered a very

rare

variant of the #47,

and it's surprising

the thing was never offered this way (and on the #46, too). There is a problem with

both the planes when

using the narrowest cutter - only one spur, the rightmost

(carried on the main

casting), can be used as it's impossible to move the

sliding section close

enough to align with the cutter's leftmost edge. This is

obviously suboptimal.

On the one example I unearthed, Stanley milled an extra

recess on the left side

of the main casting for an auxilary spur thus making it

possible to remove the

spur from the sliding section and placing it in the main

casting (you can see

the extra recess in the image to the right - the recess is

directly below the

flat milled area). The narrowest cutter now has a spur

aligned with either side

of the cutter, making the plane function as it should.

Perhaps Stanley found

this milling too costly, and it seems odd that only one

example has turned up,

which suggests that maybe it was a custom order by a

smart-thinking tradesman.

Like the #46,

these planes work marvelously for dadoing and do so

without the risk of ripping

your fingers to shreads like those 'lectrical ones can.

The #47

isn't encountered nearly as often as the #46 is, and it's a plane

that gets little respect by collectors and users. Do your

part to change this

by adopting one that happens along your way.

The following cutters come with the plane:

Cutters First Offered in 1876

|

dado |

3/8", 1/2", 5/8", 7/8", 1 1/4" |

Cutter First Offered in 1884

|

slitting cutter |

V-shaped (same as that of the #45) |

Cutter First Offered in 1919

|

dado |

13/16" |

Hey, there's that funky and whacky 13/16" cutter

again! JANE, STOP THIS

CRAZY THING!

#48 Tonguing and Grooving Plane, 10 1/2"L (8 3/4"L 1939 0n), 5/16"W, 2 3/4lbs, 1875-1944.

This

is one of Stanley's better

planes to use, and even the most ham-fisted power tool

junkie can handle this

plane and be amazed by its results. It works well, is

practically

indestructable, and is very versatile - it is designed to

work stock from

3/4" to 1 1/4" in thickness (the groove centers on stock

7/8").

The only general negative about the plane is that its tote

is all metal, which

makes for some discomfort when using the plane in colder

weather - metal sucks

the heat right out of your hands.

This

is one of Stanley's better

planes to use, and even the most ham-fisted power tool

junkie can handle this

plane and be amazed by its results. It works well, is

practically

indestructable, and is very versatile - it is designed to

work stock from

3/4" to 1 1/4" in thickness (the groove centers on stock

7/8").

The only general negative about the plane is that its tote

is all metal, which

makes for some discomfort when using the plane in colder

weather - metal sucks

the heat right out of your hands.

There are two separate lever caps, one on each side

of the main casting, to

hold the cutters in place. They are both activated by

dedicated knurled screws.

Examine these lever caps for any damage since they are

somewhat fragile. The

most common damage to them is breakage down where the cap

places pressure on

the cutter. Make sure that ends of the lever caps are not

flared away from the

main casting too much. If they are, the plane is apt to

choke since the shaving

can become lodged between the lever caps and the main

casting. I can't recall

seeing a plane with the lever caps butted perfectly against

the main casting -

they all have some degree of flaring to their lever caps -

but some flare more

than others. The nickel plated models seem to have lever

caps that flare

outward more than the earlier japanned models do.

This plane normally is found with just two cutters,

each 5/16" wide.

The original cutters of these planes do not have a circular

notch cut on their

right side up toward the top. If you see one that does, it's

a cutter from a

later #45;

the notched cutters fit the plane perfectly and work as

well as non-notched

ones, but if you're into originality you'll need to find a

cutter without the

notches.The early #45's cutters don't have the

cutout, and if one of

these are used as a replacement cutter, it's impossible to

tell whether the

cutter is original to the plane.

An extra wide cutter (5/8") was also shipped with

this plane, making

for a total of three cutters on complete examples. The wide

cutter is

positioned into the right side of the plane so that it can

cut tongues on

thicker stock. If this cutters isn't with the plane anymore,

you can still cut

tongues on wide stock, but you'll need to remove the narrow

strip of remaining

wood on the rightmost side of the wood with a small bench

plane or whatever

else you use for lightweight trimming.

To the left of the cutters is a fence, which can be

rotated end for end

about its midpoint. There is a little locking pin on the

forward portion of the

main casting, just below the knob, which engages the fence

to lock it in

position. Check that this pin is there and that it works

properly (there is a

coil spring on the pin to keep it in place). When the fence

is locked in one

position, both cutters are exposed, and, thus, cut the

tongue. When the fence

is swung end for end, and locked into its other position,

only one cutter is

exposed, which then cuts the groove.

The fence can sometimes become wobbly from years of

use. On these planes

there is generally evidence of a quick fix, where the screw

that holds the

fence to the main casting is munged from over-tightening.

You can also find

washers jammed between the fence and main casting to make

the fence steady.

There is a turned rosewood knob on the front of the

plane, and a cast closed

tote, both of which allow the plane to be worked easily. The

knob is prone to

chipping about its base, and you'll sometimes find some hack

repair jobs to the

nut and rod that fastens the knob to the main casting. The

early models of the

plane, those that are japanned, have the characteristic bead

turned at the base

of the knob.

The plane, when put in

full production, was japanned, with brass lever cap screws

(for the cutters).

Most of these earlier japanned models have the patent date,

"PAT JULY 6,

1875", depressed below the handle. A few of the earliest

japanned models

do not have the depressed date, but, instead, have "PATENTED

/ JULY 6.

1875 stamped into the sole on two lines. The date on these

earliest planes is

very tiny and is not noticeable with a casual glance.

However, the fence on the

earliest model is about 2/3rd's the thickness as that of the

more common

japanned models; the earliest being 7/16" and the later

being 3/4".

The thinner fence probably didn't offer enough lateral

stability to the plane

during use, and thus was increased to the thicker 3/4". The

earliest

planes have a pronounced bead turned at the bottom of the

rosewood knob.

The plane, when put in

full production, was japanned, with brass lever cap screws

(for the cutters).

Most of these earlier japanned models have the patent date,

"PAT JULY 6,

1875", depressed below the handle. A few of the earliest

japanned models

do not have the depressed date, but, instead, have "PATENTED

/ JULY 6.

1875 stamped into the sole on two lines. The date on these

earliest planes is

very tiny and is not noticeable with a casual glance.

However, the fence on the

earliest model is about 2/3rd's the thickness as that of the

more common

japanned models; the earliest being 7/16" and the later

being 3/4".

The thinner fence probably didn't offer enough lateral

stability to the plane

during use, and thus was increased to the thicker 3/4". The

earliest

planes have a pronounced bead turned at the bottom of the

rosewood knob.

Ca. 1900, the plane was nickel-plated, and is the

most commonly encountered

version of it. These nickel plated planes can be found with

and without the

floral motif cast into the tote; the earlier nickel plated

models have the

vines, while the later nickeled models have the fish scale

pattern cast into

the tote. World War II era planes are japanned due to the

shortage of nickel,

and are fairly scarce. It's very easy to distinguish the

earlier japanned

models from the later World War II japanned models - the

earlier models have a

vine decoration cast into their totes whereas the World War

II models have the

fish scale-like casting to them. Further, the World War II

models don't have

any patent date information on them.

During this plane's production, and the #49's as well, it was equipped

with more variations of

lever cap screws than perhaps any other plane made by

Stanley. Nicely knurled

brass screws, slotted brass screws, nickeled screws cast

with coarse knurling,

nickeled screws with fine knurling, and slotted trumpet

horn-shaped nickeled

screws can all be found on these planes. The order in

which they are listed

appears to be the chronology in which Stanley used them.

Only the japanned

models used the brass screws.

There are some very scarce models of this plane, made

by Union Manufacturing

Company of New Britain, Connecticut, which Stanley modified

and then sold under

their name (Stanley had a 'incestuous' relationship with

Union and finally

bought out their entire plane line ca. 1920). These planes

resemble the later

nickel plated Stanley-manufactured #48's,

but have black japanning in the depressions of the tote

and the fence. Stanley

ground off the UNION name (cast in the handle) and their

model numbers (cast in

the fence) from the plane, and then filled the areas with

the japanning.

Remnants of the Stanley decal can sometimes be found

applied to the japanned

area of the handle. They also did the same treatment on

the narrower #49's made by Union.

An early 'prototype', which may have served as the

inspiration for this

plane, is cast with an integral fence; i.e., it doesn't flip

end for end. It

has much more detailed floral motifs cast into it than the

conventional models

of this plane. This plane was patented by Charles Miller,

the same guy who

designed the famous #41 through #44, and the first model #50. Miller, undoubtably,

had to be familiar with the

wooden match planes that have both the tongue and groove

functions built into

them, and from these he likely modeled this metallic

prototype.

#49 Tonguing and Grooving Plane, 10"L (9"L 1937 on), 3/16"W, 2 3/4lbs, 1877-1944.

This plane is identical to the #48, except for the width of its cutters, each of which measures 3/16" wide (it, too has an extra and wider cutter so that it can work thicker stock). It is designed to work stock 3/8" to 3/4" thick, and centers its groove on stock 1/2" thick. It's less common than the #48. Like the #48, the early models are japanned, with the later ones nickel plated. The true type 1 has the patent date stamped into the sole of the plane, not depressed in the casting directly below the tote. I can't recall seeing a japanned World War II model of this plane, but I'm sure they must exist.

The plane was shortened by about an inch during the

late 1930's. These

shorter examples are not found nearly as often as the

earlier and longer

examples. Furthermore, the planes really aren't as long as

the propaganda claim

(which I use as a reference above). They are really closer

to 8" long.

These short planes have the smaller, slotted, trumpet

horn-shaped, and nickel

plated screws.

#50 Adjustable Beading Plane, 9 1/4"L, various widths, 3 1/2lbs, 1884-1962.

This

is another combination

plane, though not nearly as complex, nor heavy, as the #45. When it

was offered in its first full production, it was done so

only as a beading

plane, but someone got clever and decided it could also

function as a ploughing

plane with little modification. The plane seemed always to

be in a state of

change, as Stanley was adding this or changing that on the

tool over its

lifetime of production. Since there are numerous parts to

this plane, and

because it didn't come packed in a rugged box - cardboard

was the common

material, but there was a short time when it was offered

in a metallic box -

the plane is often found missing parts.

This

is another combination

plane, though not nearly as complex, nor heavy, as the #45. When it

was offered in its first full production, it was done so

only as a beading

plane, but someone got clever and decided it could also

function as a ploughing

plane with little modification. The plane seemed always to

be in a state of

change, as Stanley was adding this or changing that on the

tool over its

lifetime of production. Since there are numerous parts to

this plane, and

because it didn't come packed in a rugged box - cardboard

was the common

material, but there was a short time when it was offered

in a metallic box -

the plane is often found missing parts.

The plane has two threaded arms that are screwed into

a main stock. There

are holes at the end of each arm to permit a nail, or

something similar, to

tighten the arms to the main stock. Only one set of arms,

about 7" long,

come equipped with the plane (the first model of the plane

has shorter arms,

about 5" long). The arms carry a simple cast fence that is

secured with

screws (the earlier are brass flat-headed, the later are

nickel plated thumb

screws) at the appropriate distance for the cut. The fence

never was offered

with a wooden face, like those on the later #45's.

The main stock doesn't

carry the cutter so much as it butts against the cutter's

right edge. A sliding

section, similar to the function of the #45's, and roughly one half the

length of the main

stock, fits onto the arms and butts against the cutter's

left edge. The two

castings, therefore, sandwich the cutter. The way the two

castings keep the

cutter locked firmly in place is via a thumb screw. The

thumb screw fits onto a

threaded rod that's fixed into the sliding section. The

threaded rod pokes

through the main stock, and it's there that the thumb

screw makes contact with

the main stock. This thumb screw pulls the sliding section

toward the main stock

as the thumb screw is tightened. It's a rather primitive,

albeit effective, way

of holding the cutter in position, and the hassle of

trying to align the cutter

so that it sticks out just beyond (to the left and right

of) the 'skates' is

solved automatically with this design.

The main stock doesn't

carry the cutter so much as it butts against the cutter's

right edge. A sliding

section, similar to the function of the #45's, and roughly one half the

length of the main

stock, fits onto the arms and butts against the cutter's

left edge. The two

castings, therefore, sandwich the cutter. The way the two

castings keep the

cutter locked firmly in place is via a thumb screw. The

thumb screw fits onto a

threaded rod that's fixed into the sliding section. The

threaded rod pokes

through the main stock, and it's there that the thumb

screw makes contact with

the main stock. This thumb screw pulls the sliding section

toward the main stock

as the thumb screw is tightened. It's a rather primitive,

albeit effective, way

of holding the cutter in position, and the hassle of

trying to align the cutter

so that it sticks out just beyond (to the left and right

of) the 'skates' is

solved automatically with this design.

There is one slight problem with this design of

sandwiching the cutter

between two castings to hold the cutter in place, and that

is that the

narrowest two ploughing cutters (1/8" and 3/16") aren't wide

enough

to be secured in this manner. A holding screw was added when

these two cutters

were provided starting ca. 1936. The holding screw has a

head that measures

3/4" in diameter, and it's this wide head that holds the

cutter in place;

the sliding section is removed, and the holding screw is

substituted. The same

wing nut that pulls the sliding section up against the left

edge of the cutter

also pulls the holding screw's head against the left edge of

the cutter. The

holding screw is normally MIA.

Sometimes, the sliding

section doesn't; i.e. it doesn't want to move easily when

inserting or removing

the cutters. The wing nut can pull the sliding section

toward the main stock

effectively, but there wasn't any fine adjuster to push the

sliding section

away from the main stock for the times you wanted to insert

a wider cutter.

Stanley solved this problem with the addition of a small,

slotted screw at the

rear of the sliding section. The end of the screw butts

against the main stock,

and as it's turned to the right, the sliding section is

thrusted away from the

main stock. It's the combination of the two screws - one to

pull the sliding

section toward the main stock, and one to push the sliding

section away from

the main stock - that permits the fine tweaking of the tool

when changing

cutters. This little screw also controls the sliding section

so that it's

parallel with the main stock; manual adjustment can cause

the sliding section

to become misaligned on the rods, as many of us who've

goofed with the #45 know.

Sometimes, the sliding

section doesn't; i.e. it doesn't want to move easily when

inserting or removing

the cutters. The wing nut can pull the sliding section

toward the main stock

effectively, but there wasn't any fine adjuster to push the

sliding section

away from the main stock for the times you wanted to insert

a wider cutter.

Stanley solved this problem with the addition of a small,

slotted screw at the

rear of the sliding section. The end of the screw butts

against the main stock,

and as it's turned to the right, the sliding section is

thrusted away from the

main stock. It's the combination of the two screws - one to

pull the sliding

section toward the main stock, and one to push the sliding

section away from

the main stock - that permits the fine tweaking of the tool

when changing

cutters. This little screw also controls the sliding section

so that it's

parallel with the main stock; manual adjustment can cause

the sliding section

to become misaligned on the rods, as many of us who've

goofed with the #45 know.

Both the main stock and the sliding section have

spurs for working against

the grain; the spurs can be positioned out of the way when

they are not needed.

On the earlier examples of the tool, the single-lobed spurs

are rotated up 90

degrees where they sit flush to their respective 'skates'.

On later examples,

the spurs are removed from their 'skates' and are then

fastened into separate

cast depressions located on the right side of the main

stock.

The first full production planes are japanned, have

the decorative floral

motif (identical to that of the #48, #78, et al) cast into the handle,

and have no depth

stop. Ca. 1890, the plane was nickel plated, while

retaining the floral motif.

Ca. 1910, the floral motif was dropped for the common

fish-scale pattern, and

it's at this time that plane became more general purpose

by the addition of the

ploughing cutters. During the second World War, the planes

were japanned due to

the shortage of nickel, and it's possible to find planes

fitted with a mix of

finishes; i.e., a japanned fence on a nickeled body.

Starting around 1945 it

was offered with a rosewood tote until the end of its

production when hardwood

was substituted as the handle.

In 1936, a little lever was added to the plane behind

the cutter. This

lever, very much like that used on the #78, engages the cutter so that it

can be adjusted

easier. Whenever the cutter's set is changed, it's a good

idea to back off the

thumb screw so that the cutter can move more freely,

otherwise you can bend the

adjusting lever. The addition of the adjusting lever makes

it impossible for

cutters from a #45 or #55, and even earlier #50 cutters, to work in this plane

since they aren't

machined with grooves to engage the lever.

Around 1900, a chip

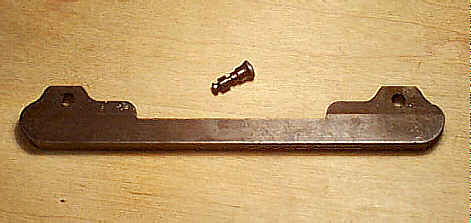

deflector (pictured to the left, with the cutter securing

bolt to the right)

was added to the plane. As the name implies, the chip

deflector's purpose is to

throw the shaving to the right of the plane instead of it

going straight up the

iron, increasing the likelihood of the plane choking with

shavings. The chip

deflector fits into the small hole just above the mouth and

to the right side

of the main casting. The first planes to be shipped with the

chip deflector

have one slight problem - the deflector and the depth stop

can't be used

simultaneously since they both fit into the same hole of the

main stock. Stanley

soon corrected this oversite by adding a provision for the

depth stop on the

sliding section ca. 1910. The most commonly missing part for

these planes,

without a doubt, is the chip deflector. They, and all the

cam rests, #278 fences, #66 parts, #67

universal spokeshave parts, etc., are all resting

comfortably in the land of

misfit parts.

Around 1900, a chip

deflector (pictured to the left, with the cutter securing

bolt to the right)

was added to the plane. As the name implies, the chip

deflector's purpose is to

throw the shaving to the right of the plane instead of it

going straight up the

iron, increasing the likelihood of the plane choking with

shavings. The chip

deflector fits into the small hole just above the mouth and

to the right side

of the main casting. The first planes to be shipped with the

chip deflector

have one slight problem - the deflector and the depth stop

can't be used

simultaneously since they both fit into the same hole of the

main stock. Stanley

soon corrected this oversite by adding a provision for the

depth stop on the

sliding section ca. 1910. The most commonly missing part for

these planes,

without a doubt, is the chip deflector. They, and all the

cam rests, #278 fences, #66 parts, #67

universal spokeshave parts, etc., are all resting

comfortably in the land of

misfit parts.

The depth stop for this plane differs from that used

on the other

combination planes like the #45. The earlier #50's depth stop has its post

centered on the foot

whereas the #45's has its post offset toward

one side (the front)

of the foot. Later #50's have

the post offset toward the front of the foot, but the foot

is longer than those

of the #45. The post on the #45's stop has a larger diameter

than the #50's. Check that a #45 stop hasn't been modified to

fit the #50.

To compound the confusion, Stanley equipped the

plane with a beading stop starting around 1915; planes

made after this date

actually have two stops, with the beading stop being

longer than the common

depth stop. The beading stop is used just like the one for

the #45 is.

The plane doesn't have steel skates like the #45 does. Instead, it has cast

iron skates, like the #46, which are integral

to the main stock and the sliding section. As is the case

with any cast iron,

check it carefully for cracks, welds, breaks, etc. Look

around the main stock,

where the cutter engages, for any stress cracks. This can

be a problem area,

and Stanley took measures to overcome the flaw with the

addition of a

reinforcement rib cast into the right side of the main

stock ca. 1935.

The following cutters come with the plane:

Cutters First Offered in 1884

|

beading |

1/8", 3/16", 1/4", 5/16", 3/8", 7/16", 1/2" |

Cutters First Offered in 1902

|

grooving |

1/4" |

|

tonguing |

1/4" |

Cutters First Offered in 1914

|

ploughing |

5/16", 3/8", 7/16", 1/2", 5/8", 7/8" |

Cutters First Offered in 1936

|

ploughing |

1/8", 3/16" |

There is

another plane that has the same number designation as this

one. This particular

plane was not offered by Stanley as a #50,

but was, instead, offered as that model number by the

Russell & Erwin

Manufacturing Company of New Britain, CT. It's generally

thought that Stanley

made the planes for Russell & Erwin, who sold them as

Miller's Improved

Joiner's Plow, the No. 50. It is possible

that Stanley designated

the plane as the #50,

since it

pre-dates the common configuration of the #50, but no advertising literature

has surfaced to

indicate that Stanley actually sold it. Stanley was

manufacturing the #41-#44 Miller's

Patent series concurrently to this plane, and perhaps they

didn't want to

advertise a plane that did the same function as those. Who

knows? Regardless,

the plane wasn't manufactured for long, probably as a

result of its delicate

castings which certainly must have proved to be difficult

to make.

There is

another plane that has the same number designation as this

one. This particular

plane was not offered by Stanley as a #50,

but was, instead, offered as that model number by the

Russell & Erwin

Manufacturing Company of New Britain, CT. It's generally

thought that Stanley

made the planes for Russell & Erwin, who sold them as

Miller's Improved

Joiner's Plow, the No. 50. It is possible

that Stanley designated

the plane as the #50,

since it

pre-dates the common configuration of the #50, but no advertising literature

has surfaced to

indicate that Stanley actually sold it. Stanley was

manufacturing the #41-#44 Miller's

Patent series concurrently to this plane, and perhaps they

didn't want to

advertise a plane that did the same function as those. Who

knows? Regardless,

the plane wasn't manufactured for long, probably as a

result of its delicate

castings which certainly must have proved to be difficult

to make.

This plane is a masterpiece in Victorian tool design

and the art of casting

and is one of the most prized objects in all of tooldom. The

plane is

elaborately cast with floral designs on its fence and main

stock. There is a

tiny turned rosewood knob fixed to the front left portion of

the sliding fence.

It can be found cast in iron and gunmetal, but with subtle

design changes to

each depending upon the material used to cast it - the most

obvious difference

is that the gunmetal castings have a pierced skate of

scrolled motifs whereas

the iron castings have a stippled skate. The gunmetal

version also lacks the

'bridge' that spans the curved portion of the fence casting,

between the two

arms. The cast iron version was plated with a copper-colored

surface, which is

usually long gone when these planes rarely show.

#51 Chute Board Plane, 15"L, 2 3/8"W, 7 1/8lbs, 1909-1943.

This is an L-shaped plane

(in cross-section), with a skewed blade (relative to the

sole), and is designed

to clean up mitres on finer work. It has the typical Bailey

adjustment

mechanism, and a rosewood tote, but no turned rosewood knob.

The tote is nearly

impossible to grip with your left hand due to its position

on the casting and

its leaning to the right. It also can be tough to grip with

your right hand, if

you have hands that are the size of Sasquatch's. The tote is

the same size as

those used on the larger Bailey bench planes, and can be had

from one of those

planes if your tote is damaged.

This is an L-shaped plane

(in cross-section), with a skewed blade (relative to the

sole), and is designed

to clean up mitres on finer work. It has the typical Bailey

adjustment

mechanism, and a rosewood tote, but no turned rosewood knob.

The tote is nearly

impossible to grip with your left hand due to its position

on the casting and

its leaning to the right. It also can be tough to grip with

your right hand, if

you have hands that are the size of Sasquatch's. The tote is

the same size as

those used on the larger Bailey bench planes, and can be had

from one of those

planes if your tote is damaged.

The body of the plane is ground square so that it can

cut accurately as its

sole rides on a flat surface. The plane was designed to be

used with the chute

board, #52, but

could be purchased separately by those guys who had a

board of their own.

The frog is a custom shape - you can't take a regular

Bailey frog and make

it fit this one, if your frog is screwed up. The frog is

screwed to a rather

thick cross-bar in the main casting of the plane's body.

Check that this

cross-bar isn't cracked. Because the frog doesn't mate to

the main casting like

a conventional bench plane's does, it's impossible to open

or close the mouth

of the plane. Further, a good portion of the cutter is

unsupported because of

the frog's design. The cutter is supported where it's most

important, down at

the mouth, but for the plane to work as intended, the cutter

needs to be very

sharp since a good amount of the tool's use is cutting

across the grain. And,

speaking of the mouth, its right side (when viewed from the

sole) terminates in

a circular fashion

The lateral lever, common on all the Bailey bench

planes, plays an important

role for this plane in the patternmaking trade. The lever

can angle the iron,

relative to the sole, by the desired amount to give the work

being planed the

proper draft. Draft is a very important part of

patternmaking; draft is the

slight angle given to a pattern so that the resulting

casting can pop free from

the sand.

This plane has been observed fitted with the typical

World War II

treatments; i.e., hardwood tote, hard rubber adjustment nut,

no nickel plating

on the lever cap, etc. If you find yourself in need of a

replacement cutter or

lever cap, both are identical to those used on a #6 and #7.

#52 Chute Board and Plane, 22"L, 9"W, 35lbs (17 1/2lbs 1909 on), 1905-1943. *

This

is Stanley's offering of the

#51 plane along

with a heavy cast iron chute board, which is designated

the #52.

Together, the two pieces sort of resemble a meat

slicer in appearance (it slices and dices ok, but don't

buy it to julienne).

These two parts work very well, but are, unfortunately for

the user, very

expensive.

This

is Stanley's offering of the

#51 plane along

with a heavy cast iron chute board, which is designated

the #52.

Together, the two pieces sort of resemble a meat

slicer in appearance (it slices and dices ok, but don't

buy it to julienne).

These two parts work very well, but are, unfortunately for

the user, very

expensive.

Stanley advertised the board and the plane as being

useful for

patternmakers, cabinetmakers, printers, picture framers, and

electrotypers.

They even make a specific mention that "amateurs will also

find this tool

very useful." During the early 1920's, the board and plane

were priced at

$23.45. A common #5 was priced $6.05. It seems that there must have

been some yuppy

woodworker types even back then or Stanley wouldn't have

mentioned the plane's

amateur use in its propaganda.

The board is machined flat, and has a track into

which the plane rides. The

plane can sometimes stick in its track due to shavings and

crud piling up in

the track, and for the plane to cut accurately and

effortlessly, this track

needs to be clean. A drop of oil along it also keeps the

plane sliding along.

If you still find the plane tracking with difficulty, you

can adjust the

metallic strip along the right edge of the board. There are

four screws that

allow the strip to be adjusted latteraly when they are

loosened; just loosen

the screws, set the plane in the track, butt the strip

against the rightmost

edge of the plane, and then tighten the screws in a linear

fashion as you move

the plane along the entire length of the track

The surface of the board is ground flat and left

unfinished, but the

depressions cast into the board are japanned. The number

"52" is cast

into a depression of the track. The earliest models have the

1896 patent date

cast into them. There are two countersunk holes bored into

the beginning and

end of the track. These holes allow the board to be attached

to a piece of wood

for mounting it in a fixture or on the bench. The board also

has several holes

bored in it to accomodate the adjustable stop. Three of the

holes are

predefined positions for the common angles of 90, 60, and 45

degrees; each of

these holes has the degree incised near it. Into these

predefined positions a

t-shaped pin fits to make adjusting the stop easy. This

t-shaped pin is often

missing from the board.

There is a stop on the

board, which can be adjusted through an arc of 45 degrees

(degree markings are

incised along the arch-shaped portion of the stop). There

are two holes in the

board at which the stop screw can be positioned; at the

first hole the stop can

be adjusted from 45 to 90 degrees, while at the other the

stop can be adjusted

from 45 to 0 degrees. Check the arched portion of the stop

for any signs of

cracks, as it is susceptible to stress from the force

applied to it by the

locking screw.

There is a stop on the

board, which can be adjusted through an arc of 45 degrees

(degree markings are

incised along the arch-shaped portion of the stop). There

are two holes in the

board at which the stop screw can be positioned; at the

first hole the stop can

be adjusted from 45 to 90 degrees, while at the other the

stop can be adjusted

from 45 to 0 degrees. Check the arched portion of the stop

for any signs of

cracks, as it is susceptible to stress from the force

applied to it by the

locking screw.

Attached to the stop is a plate that slides

latterally relative to the

track. This plate is adjusted based upon the setting of the

stop so that the

wood can have the proper support behind it as it is planed.

When the stop is

adjusted from 90 degrees to 45 degrees, the plate is slid

away from the track

lest the plane slam into it during operation. The plate is

locked in place with

a nickel plated wing nut.

Attached to the face of the plate is an L-shaped hold

down clamp. This clamp

is locked in position with the same kind of thumb screw as

that used to secure

the plate. The clamp is provided to hold the workpiece in

position as it is

shot true. The clamp has a hole drilled into it so that a

screw may be driven

into the workpiece for real holding power. The clamp is

often missing on these

boards, and its absence greatly diminishes the value (for

collectors) of the tool.

Since this tool is designed to be very accurate, look

for any signs of

cracks and repairs anywhere on the board and plane.

#53

There ain't one. A plane, that is. There is a common as mud spokeshave that's numbered 53, but that's another subject for another day.

#54 Plow and Rabbet Plane, 9 1/4"L, various widths, 3 1/4lbs, 1939-1949. *

Only Stanley knows the reason why this plane was put into production as its utility is rather limited. Perhaps Stanley recognized the void in their numbering system, and decided that they ought to fill it with something useless. Or maybe they needed a plane to preceed (in the numbering sequence) that ghastly beast, the #55, in order to numb the potential customers as they scanned the company's catalogs. Whatever the reason, the plane didn't sell well and it's one of the scarcer planes in Stanley's former product line.

It's just another combination plane, whose appeal was

limited due to its

specific use. It really is a redundant plane, since it's

identical to the #50, except that there

is no depth stop provided on the sliding section (this

plane suffers from a

classic case of identity crisis); there is a "vestigal"

bulge on the

sliding section that's not tapped for the depth stop and

its locking screw. The

plane does use the depth stop on the right side.

Since the plane is designed only to groove/rabbet

with the grain, it has no

need for spurs, and there is no holder for the spurs cast

into the right side

of the main stock. If this isn't enough to identify your

plane, the sliding

section has the number cast into the arched portion.

The tool propaganda Stanley provided with this tool

states that it came

equipped with two pair of arms, one short pair and one long

pair. When the

plane is found, it's usually done so with just one pair of

arms. The plane came

fully nickel plated, but some japanned models were produced

during the war

years and it's possible to find mix and matched parts where

the main stock is

nickeled and the fence is japanned, for example.

The plane has the same cutter adjustment lever as

that provided on the #50. Some recent tool

literature states the plane came without the adjustment

lever during its first

years of production. I can't ever recall seeing one

configured this way, and

given the fact that the plane debuted a few years after

the debut of the #50's cutter adjustment

lever, a convincing argument that the #54 was offered only with the adjustment lever can be

made since modified #50 bodies were used for

this plane.

The following 8 ploughing irons come with the plane:

Cutters First Offered in 1939

|

ploughing |

1/8", 3/16", 1/4", 5/16", 3/8", 7/16", 1/2", 5/8" |

[ START ] |

[ PREV] | [ NEXT

] | [ END ]

[ HOME

]

Copyright

(c) 1998-2012 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved.

No part may be

reproduced by any means without the express written

permission of the author.