The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #201 - #444

Quick Find: #201, #203, #205, #212, #220, #238, #239, #239 1/2, #248, #248A, #271, #278, #282, #283, #289, #292, #340, #378, #444

Hah, just when you thought all of Stanley's plane

guts were strewn about the

information superhypeway, along comes some more road pizza.

This time, there

are some bloody sights to behold....

#201 Block plane, 3 1/2"L, 1"W, 1/4lb, 1906. *

This plane is identical to the #101, the toy-size block plane, except for its finish. This one is nickel plated, whereas the #101 is japanned. Collector alert - watch for re-plated #101's passed off as real #201's.

#203 Block plane, 5 1/2"L, 1 3/8"W, 1 1/8lbs, 1912-1962.

A smaller block plane

designed primarily for manual training use. The plane is

somewhat scarce due to

its size and lack of bells and whistles. The same problems

one can find on the

common block planes, like chipped/cracked mouths, stripped

adjusters, cracks in

the lever cap, etc., can also be found on this plane,

especially on those that

were on the receiving end of junior's abuse.

A smaller block plane

designed primarily for manual training use. The plane is

somewhat scarce due to

its size and lack of bells and whistles. The same problems

one can find on the

common block planes, like chipped/cracked mouths, stripped

adjusters, cracks in

the lever cap, etc., can also be found on this plane,

especially on those that

were on the receiving end of junior's abuse.

This plane has its cutter pitched at 20 degrees, and

has a cutter adjustment

mechanism like that found on the #60, et al, although the sliding

part of the adjuster

is not the same as that used on the low angle block planes

but is like those

used on the #220. The plane might be mistaken for the first model

of the #60 (those

without adjustable mouths) were it not for the pitch of

the cutter and the fact

that "203" is usually cast below the cutter's adjustment

knob.

There is no provision for mouth adjustment; i.e., the

sole is one piece. The

front knob is turned rosewood (on the earlier planes) or

hardwood (on the later

planes). The knob threads onto a threaded boss, and should

you be in need of

one, you can snag one off a #110, #120, #140 (although the tool police

might put you up against

a wall and ask why you would want to take a knob off a

more valuable plane to

put on a cheaper one), and #220, et al.

Although this is a nice, functional plane, you may

choose to leave this

plane for the kiddies, and get a larger one for the mature

and muscular you.

#205 Block plane, 6 1/4"L, 1 3/8"W, ~1lb, 1927-1934.

This is a piece of junk that only a collector, when overtaken by a fit of momentary insanity, would ever dare own. Forget it as a user tool, since it's garbage. It was offered in a boy's tool set, but never as a separate plane, in Stanley's catalogs. It was offered separately in other catalogs (hardware firms), which ought to indicate that even Stanley was embarassed with this ugly baby.

The plane is pressed steel, and has a projecting

steel palm grip which is

fastened to the bottom. A cheesy cutter securing mechanism

is nothing but a

screw through a slotted hole in the cutter. The cutter is

marked

"DEFIANCE", which says to me, whenever I see this plane, "I

defy

you to buy me." Stay away from it, it's quicksand! Heck,

it's not even

worthy as a projectile when you're looking for something to

throw at your

neighborhood's stray cats.

#212 Scraper plane, 5 1/2"L, 1 3/8"W, 1 1/2lbs, 1911-1934. *

A very small scraper

designed for very small work, with very small sales, all of

which make it quite

rare. It's sorta the #1 of scrapers. It has the exact

same blade adjustment

mechanism as that found on its larger siblings, the #12 and #112 which

ultimately inspired its design, only this one has a scaled

down version.

Instrument makers (Stanley specifically mentioned violin

makers in their

propaganda), flyrod makers, etc., were the people who may

have found this plane

useful.

A very small scraper

designed for very small work, with very small sales, all of

which make it quite

rare. It's sorta the #1 of scrapers. It has the exact

same blade adjustment

mechanism as that found on its larger siblings, the #12 and #112 which

ultimately inspired its design, only this one has a scaled

down version.

Instrument makers (Stanley specifically mentioned violin

makers in their

propaganda), flyrod makers, etc., were the people who may

have found this plane

useful.

It has a turned knob, made of rosewood, similar to

that found on a common

bench plane. There are some scarcer models that have a knob

turned of mahogany.

These knobs tend to be a bit more elongated than the

rosewood version,

something you can't tell unless you've seen both. The knob

is mounted at the

rear of the casting, sitting atop an inclined boss of the

casting, and is

oriented so that it leans backward to give the workman a

better grip - it fills

the palm of his hand. The knob is attached with the common

two-piece rod and

brass nut.

The tool has the Hand-y feature milled into the sides

just like that found

on the block planes, but the milling is longer than that

done on the block

planes. I've seen an example where the sides were chopped

down to below the

Hand-y grip for some unfathomable reason.

The 'frog' (blade clamping assembly) is attached to

the main casting via a

slotted screw that's been machined flush with the sides of

the tool. The

pivoting section of the frog uses a similar screw to attach

it to its corresponding

part. Check the casting of the pivoting section, where the

screw passes through

it, for any sign of cracks or repairs. Also check where the

threaded rod joins

the 'frog' for signs of damage.

This plane has been reproduced two times. The first

time in an attempt to

fool the collectors. It's a poor job, and isn't nearly as

good as the #1's

reproduction. The second reproduction is not done in an

attempt to deceive

anyone, but is done as a modern working tool. This latter

reproduction is cast

of manganese bronze, which even the untrained eye can spot

as the

distinguishing feature from an original.

These planes are very difficult to find with their

blades marked with any

Stanley logo. Consider yourself lucky if you have one. The

model number is

embossed at the toe, under STANLEY that's cast in a

'scrolled' fashion. The

lever cap screw is non-plated brass and has STANLEY RULE

& LEVEL Co. NEW

BRITAIN, CONN USA" stamped into it in fine lettering.

#220 Block plane, 7 1/2"L (7"L, 1917 on), 1 3/4"W (1 5/8"W, 1909 on), 1 1/2lbs, 1898-1973.

This plane is identical

to the #203,

except that it is larger. A more useful plane than the #203, but it's nice to

have an adjustable mouth, which this one, too, lacks.

Weren't those guys at

Stanley considerate by offering us such a selection of

block planes? On the

plus side, the plane is at least suitable for parts

snarfing - the rosewood

knob is identical to the one provided on the more useful,

and valuable, #140.

This plane is identical

to the #203,

except that it is larger. A more useful plane than the #203, but it's nice to

have an adjustable mouth, which this one, too, lacks.

Weren't those guys at

Stanley considerate by offering us such a selection of

block planes? On the

plus side, the plane is at least suitable for parts

snarfing - the rosewood

knob is identical to the one provided on the more useful,

and valuable, #140.

The plane is also very similar to the #120, but this one has the screw

adjusting mechanism and

sliding cutter seat that are used liberally on the low

angle block planes of

the #60 series. The lever cap is interchangeable with all

the adjustable block

planes that have the same width iron, like the #9 1/2, which

also have the lever cap screw. The earlier examples will

have the nickeled cast

iron adjusting screw; the one in the image is the common

steel one with the

crosshatched knurling and incised with "STANLEY".

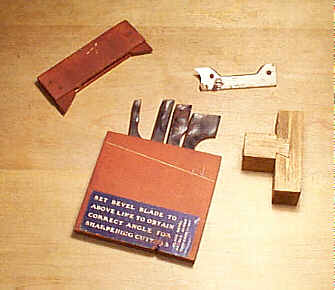

The example pictured here has the original decal on

the lever cap, which was

used during the late 1920's to the early 1930's on many of

Stanley's planes.

Planes and tools in this condition should be collected and

not used; this plane

is easy enough to find in dogmeat usable condition, so

there's no need to go

ruining a mint example of what's otherwise a bland tool.

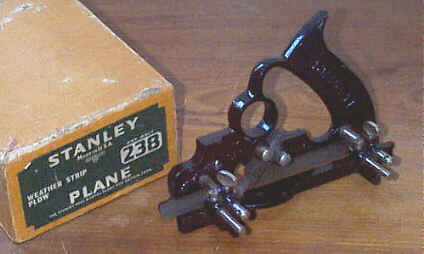

#238 Weatherstrip plow plane, 7 1/2"L (9 1/2"L, 1936 on), various widths, 1 7/8lbs, 1930-1938. *

This is a plane that

none of us will ever likely use. It was designed to cut the

grooves in window

sash for the installation of weatherstripping. It really is

an ugly little

monster, and is characterized by a circular hole in the main

casting, which

accepts your first finger when gripping the plane. There's

plenty of room for

all four fingers to wrap around the tote, and it seems

strange that Stanley

provided this circular hole for finger comfort. Anyone out

there have a

surviving relative who once labored in the weatherstripping

trade what won't

mind your checking their meathooks?

This is a plane that

none of us will ever likely use. It was designed to cut the

grooves in window

sash for the installation of weatherstripping. It really is

an ugly little

monster, and is characterized by a circular hole in the main

casting, which

accepts your first finger when gripping the plane. There's

plenty of room for

all four fingers to wrap around the tote, and it seems

strange that Stanley

provided this circular hole for finger comfort. Anyone out

there have a

surviving relative who once labored in the weatherstripping

trade what won't

mind your checking their meathooks?

A tiny depth stop is positioned just forward of the

cutter - it measures

just 7/8" long. Seven cutters were provided with this plane

- 1/8",

5/32", 3/16", 7/32", 1/4", 5/16", and 3/8". These

cutters sorta look like the cutters a machinist uses in a

lathe. The right edge

of the cutter aligns with the right side of the skate.

If the plane's design, and function, aren't weird

enough for you, certainly

you'll find the means to secure the cutter to be among the

weirdest of any

Stanley plane. Two large slotted screws 'sandwich' the

widest portion of the

cutter. These screws are milled so that they have a smaller

diameter below the

head. The head of each screw bears down upon the cutter -

one screw forward of

the cutter, and one behind the cutter - driving the cutter

against the machined

area in the main casting. These screws each rest in a

semicircular depression

of the main casting, and these areas can suffer chipping and

cracking. Seems as

though someone at Stanley had a real bad plane design day on

this one.

The plane

carries what appears to be 4 arms, two pair of one large and

one small. There

is actually one pair of arms, each of which screw into the

main casting, and

it's on these arms that the fence is secured with smallish

nickel plated thumb

screws. Ahead of each arm is a smaller diameter rod that's

held in position

with a slotted and flat-headed screw. Both of these smaller

rods are actually

stops that allow the weatherstripping dude to make repeat

cuts when the fence

is moved; the rods slam up against the main casting to

prevent the fence from

being moved closer to the cutter. These rods are often

missing from the plane,

and unless you can figure out a good use for them, you won't

miss them if yours

doesn't have them. Sometimes, the stops are replaced (by

guys trying to make a

bland plane more attractive so that they can get them off

their table). Each

stop has a groove milled toward its end with a piece of wire

bent around and

into the groove to increase the diameter of the stop, making

it difficult for

it to slip out of the fence. Stanley must have foreseen the

likelihood of these

stops entering the same realm as cam rests, slitting

cutters, core box

turnbuckles, etc.

The plane

carries what appears to be 4 arms, two pair of one large and

one small. There

is actually one pair of arms, each of which screw into the

main casting, and

it's on these arms that the fence is secured with smallish

nickel plated thumb

screws. Ahead of each arm is a smaller diameter rod that's

held in position

with a slotted and flat-headed screw. Both of these smaller

rods are actually

stops that allow the weatherstripping dude to make repeat

cuts when the fence

is moved; the rods slam up against the main casting to

prevent the fence from

being moved closer to the cutter. These rods are often

missing from the plane,

and unless you can figure out a good use for them, you won't

miss them if yours

doesn't have them. Sometimes, the stops are replaced (by

guys trying to make a

bland plane more attractive so that they can get them off

their table). Each

stop has a groove milled toward its end with a piece of wire

bent around and

into the groove to increase the diameter of the stop, making

it difficult for

it to slip out of the fence. Stanley must have foreseen the

likelihood of these

stops entering the same realm as cam rests, slitting

cutters, core box

turnbuckles, etc.

The fence on this plane is as long as the plane

itself is. Make sure that

the portion of the fence in front of the front arm and the

portion behind the

rear arm are present and not broken. There are two holes

drilled in the face of

the fence for attaching an auxiliary fence.

The original cardboard boxes for this plane are

unusually 'spacious' when

compared to the tight fits provided on the boxes' of other

planes. Stanley made

this one deep enough so that the plane could be stored

assembled. Why? Good

question. Maybe they touted the roomy box as a cool feature

of the plane. Then

again, maybe not.

#239 Special dado plane, 7 1/2"L, various widths, 1lb (1 1/2lbs with fence), 1915-1943. *

You ready for this one? This ugly little thing, very much resembling the #238, was used for blind wire grooving, which was a fad sweeping across America. I'm sure electricians far and wide slugged it out, tooth and nail, to be the first on the block to own one. The plumbers of America surely musta felt slighted that they didn't have a plane to call their own.

This was a plane that underwent many transformations

during its too long

existence on this planet. The earliest models look just like

the #238, but without a

fence. Since some thrill seeking electrician was using the

plane across grain,

and word of that got back to Stanley, a vertical spur was

added to the plane so

that the wood would be scored before the cutter did its

cutter thing.

Electricians musta rejoiced over their clean blind wire

dados. Oh to have been

a fly on the wall at that time! Finally, a fence was added

to the plane ca.

1925 to make the plane function more like a regular

plough. Shame on Stanley

for thinking that they could pass off a crappy little

plane on the electricians

and believing that they wouldn't know any better! It took

them electricians a

little time to figure what was going on, but they finally

got what shoulda been

theirs from the get go.

The plane came in four different widths, sized by the

cutters: 1/8",

5/32", 3/16",1/4".

#239 1/2 Special dado plane, 7 1/2"L, 1/8"W, 1 1/2lbs, 1919-1923. *

Special in the sense that this is the same plane as the #239, but had a fence. The plane was dropped once some Stanley Einstein realized that the #239 should have had a fence from the start. The plane was only offered in one width - 1/8".

This is a very difficult plane to find, but only the

collectors, who have to

have one of every plane Stanley ever made, care about it.

#248 Plow plane, 9 1/2"L, various widths, 2 1/4lbs, 1936-1943.

Another in a series of forgettable planes, which shoulda never been made. This one was designed to cut grooves for weatherstripping and light ploughing. It sorta looks like the #238, except this one is elongated, doesn't have the circular opening in the casting. It has a depth stop. Only two cutters were provided with the plane - 1/8" and 5/32". Just another piece of flotsam adrift in Stanley's sea of shame.

#248A Plow plane, 9 1/2"L, various widths, 2 1/4lbs, 1939-1958.

Stanley offered this

plane as one of their ill-fated weatherstripping tools, and

it replaced the

defunct #238

while retaining the cutter securing screws used on that

dead and buried plane.

This marvel of technological advancement notwithstanding,

the plane is as

unimaginative in design as that velvet Elvis painting that

you found at a local

starving artist sale and now have hanging over your

mirrored waterbed.

Stanley offered this

plane as one of their ill-fated weatherstripping tools, and

it replaced the

defunct #238

while retaining the cutter securing screws used on that

dead and buried plane.

This marvel of technological advancement notwithstanding,

the plane is as

unimaginative in design as that velvet Elvis painting that

you found at a local

starving artist sale and now have hanging over your

mirrored waterbed.

Lucky for us Stanley didn't put the letter "A" in

front of the

number, or we woulda been stuck with the aluminum version of

the #248 (as if the mere

existence of the #248 isn't enough to suffer). Nope,

in this case, the

letter "A", as a suffix, indicates that this plane was

another mutant

of a plane that coulda been made/offered as one complete

model. The plane does

not have the letter "A" cast into it.

What's the distinguishing characteristic (from the #248) of this genetic dead end?

Nothing but the addition

of 5 cutters - 3/16", the ever popular 7/32", 1/4", 5/16",

and 3/8". The cutters (as well as the depth stop and the

stop and fence

screws) are interchangeable with those of the #238. The stops of this plane have

a different treatment

to them than the #238 does. Each stop has two little

integral burr-like

projections near the end to keep from sliding out of the

fence.

The plane is limited in the depth it can cut - up to

5/8" deep. If you

plan to use this thing, and a lot of guys like to use this

goober for lightduty

ploughing, you should check that the skate and/or the fence

aren't chipped;

both the skate and fence are the same length. The fence has

two holes drilled

into it to allow a wooden face to be attached. The plane has

a rather strange

casting for the integral handle - a web-like portion can be

found at the bottom

of each side of the handle. This area of the casting can be

found cracked or

chipped.

#271 Router plane, 3"L, 1/4"W, 3/8lb, 1926-1973.

A handy, small router

for light work. It's one of Stanley's better ideas, which

gained favor from

those doing inlay, mounting small door hardware, etc. The

plane is a flat,

rectangular casting, with a vertical portion at the midpoint

that is used as a

grip and to secure the cutter (by means of a simple slotted

screw). There are

two positions on which the cutter can be attached to the main

casting. One

position allows the tool to be used for normal work, and the

other position for

bull nose work.

A handy, small router

for light work. It's one of Stanley's better ideas, which

gained favor from

those doing inlay, mounting small door hardware, etc. The

plane is a flat,

rectangular casting, with a vertical portion at the midpoint

that is used as a

grip and to secure the cutter (by means of a simple slotted

screw). There are

two positions on which the cutter can be attached to the main

casting. One

position allows the tool to be used for normal work, and the

other position for

bull nose work.

Some guys would mount a block of wood on the tool by

tapping holes through

the casting (in the vertical portion, where you grip the

tool), and then screw

the wood to the casting. This after-market option was done so

that a better

grip could be had on the tool.

The plane is nickel plated, and is still manufactured over

in England. A

short production of japanned models was offered during WWII.

These are very

scarce, but no one, as yet, cares.

#278 Rabbet and filletster plane, 6 3/4"L, 1"W, 2lbs, 1915-1943. *

This is a dual-purpose

plane - the primary function is to cut rabbets and the other

is to confound you

over how the blessed thing is gripped without contorting

your fingers in

directions they aren't supposed to go. Ergonomics wasn't

invented yet to help

this thing be user-friendly.

This is a dual-purpose

plane - the primary function is to cut rabbets and the other

is to confound you

over how the blessed thing is gripped without contorting

your fingers in

directions they aren't supposed to go. Ergonomics wasn't

invented yet to help

this thing be user-friendly.

The plane is ground on both sides so that they are

square with the sole and

so the plane can lay flat on either side. Its iron is

pitched at ~20 degrees,

and is used bevel side up. The iron has a series of parallel

grooves machined

into its back. These grooves are engaged by a tacky-looking

pressed steel

lever, which regulates the iron's set. The iron is held in

place by a

screw-activated lever cap that's unique to this plane. Check

the lever cap for

any repairs or cracks. Also, check that the iron isn't a

crude replacement made

from a #90 - the iron on this plane is unique to this plane.

The surest way to

tell is by looking at the iron where it bulges out near

its cutting edge. An

original iron is not bevelled along the edges, whereas the

#90's is.

The first models of the plane carry irons marked "PAT.

10-17-16" on

their heels.

A detachable nose piece is provided, which makes the

tool function as a

chisel plane. The nose piece is secured to the main portion

of the plane with a

slotted screw, which often becomes mangled through repeated

use. On the nose

piece are two retractable spurs, one on each side, which are

used to score the

grain when working across the grain. There is also a very

small, and fragile,

adjustable depth stop that can be affixed to either side of

the plane. The

depth stop fits into a v-shaped groove to steady it. A small

nickel plated

thumbscrew, equipped with a washer, locks the depth stop in

place.

There's a circular

portion, about the diameter of a quarter, cast into the nose

piece. This

circular opening of the casting is supposed to provide a

grip while using the

plane, but I haven't figured out how to do it, especially

since the depth stop

sticks up beside it and restricts the room for whichever

finger you dare jam

through there.

There's a circular

portion, about the diameter of a quarter, cast into the nose

piece. This

circular opening of the casting is supposed to provide a

grip while using the

plane, but I haven't figured out how to do it, especially

since the depth stop

sticks up beside it and restricts the room for whichever

finger you dare jam

through there.

A fence rides on an arm, which can be positioned on

either side of the

plane. This fence is often missing (the depth stop is too).

The plane is sorta

valuable, so many times you'll see the plane offered with a

replacement fence

salvaged from a #78. The sure way to tell an

original #278 fence is to look at the

position of the hole for

the arm. If it's noticeably toward one side of the

casting, it's a #78 fence. In

the image of the two fences, the #278's is the one to the left. An original #278 fence has its hole centered in

the casting. There

are no other holes in the fence.

The plane is almost entirely japanned. The thumb

screws and the lever cap

screw are nickel plated. The sides of the plane are milled

and have no

japanning. However, I have had an example of this tool that

has its milled

sides nickel plated. A tool pal of mine also reports a

similar nickeled

example. It's impossible to say whether the plane was plated

at a later date or

whether someone in New Britain was goofing around with some

leftover nickel at

the end of the day.

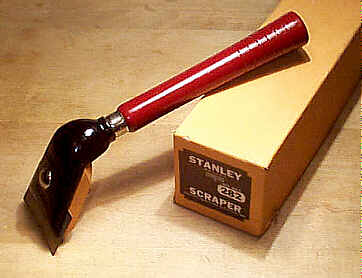

#282 Scraper, 13"L, 3"W, 1 5/8lbs, 1925-1958.

An inexpensive floor

scraper, which I've included only as filler. Forget it -

it's ugly and

worthless, now that we have those 'lectrical floor sanders

at our renting call.

Still, the chef in you might find it very useful for

scraping your cast iron

griddle clean of pancake crusties.

An inexpensive floor

scraper, which I've included only as filler. Forget it -

it's ugly and

worthless, now that we have those 'lectrical floor sanders

at our renting call.

Still, the chef in you might find it very useful for

scraping your cast iron

griddle clean of pancake crusties.

The tool is a very simple construction - a wooden

handle (unfinished maple

until the mid-1930's, and from then on red painted hardwood

until it went belly

up) is attached to a japanned casting. On the backside of

the casting is a

maple block. Through both the maple block and the casting a

bolt passes with a

large washer and thumb screw to tighten the two pieces

together. Between the

casting and the wood block is a 1 3/4" by 3" scraper blade

that

projects to either side of the main casting by about 1/4".

The chunk of

wood helps to dampen the blade as you pull the tool toward

you. The wood often

becomes all beat to hell or split from years of hard floor

scraping.

The blade is normally fixed into the holder so that

the blade's cutting edge

is parallel with the casting's leading edge. However, the

blade can be pivoted

somewhat by turning the wood block toward one side and then

tightening it.

#283 Adjustable scraper, 9 1/2"L, 2 7/8"W, 2lbs, 1930-1941. *

This is another

wierd invention of Stanley's, which really should have sold

more than it did.

It's a tough tool to find.

This is another

wierd invention of Stanley's, which really should have sold

more than it did.

It's a tough tool to find.

A turned tropical hardwood (the few I've owned are

either mahogany or cocobolo)

has a geared cast piece fitted into its business end. The

geared piece accepts

a similarly geared cast piece. Together, these two pieces

are screwed together

with a wing nut to allow the scraper blade to be adjusted

forward or backward.

The scraper blade is held in place by another wing nut, and

allows the blade to

be tilted from side-to-side. Because of the two degrees of

freedom, the scraper

can be configured for the hard to reach, awkward areas. It

was also advertised

as being useful for floor scraping, which I suppose is a

good thing for those

who are given to fits of living on their hands and knees.

The scraper blade is the typical blade used in the #12-type

scrapers, except it has a hole drilled through its center

so that it can be

attached indirectly to the handle. The Stanley logo is

stamped off-center,

toward one of the long edges of the blade. If you see one

that has the logo

situated elsewhere, be suspicious of it being a

replacement.

A wooden

grip,

as wide as the blade is wide, is kerfed to fit over the top

edge of the blade.

The grip has a metal strip screwed to it. The strip of metal

extends below the

grip and is curved so that it acts like a pressure spring to

keep the grip from

falling off. The grip can be pulled off so that the blade

can be sharpened. The

grip is often missing on the tool.

A wooden

grip,

as wide as the blade is wide, is kerfed to fit over the top

edge of the blade.

The grip has a metal strip screwed to it. The strip of metal

extends below the

grip and is curved so that it acts like a pressure spring to

keep the grip from

falling off. The grip can be pulled off so that the blade

can be sharpened. The

grip is often missing on the tool.

A washer-like cast iron piece is notched to fit

around the strip of metal.

This cast piece is what puts pressure on the blade when the

wing nut is screwed

tight. This cast iron piece has the number " No. 283" cast

into it.

Because of the length of the metal strip (attached to

the grip), and the

fact that it fits into the notch in the cast iron piece,

it's impossible to use

anymore than approximately 1.5" of the blade. The metal

strip could be

shortened by cutting it, but doing so decreases the amount

of tension it offers

to keep the grip in place. It's perhaps this design flaw,

along with the myriad

of other scrapers Stanley offered, that killed this tool

soon after it left the

drawing board.

The wing nuts have wings that are higher than normal

- sort of what you'd

expect if Mickey Mouse's ears paralleled Pinoccio's nose

whenever Mickey said

he likes the #55. The wing nuts are nickel plated, and the cast

iron parts are

japanned.

Several other manufacturers made a tool that looks

practically identical to

this one. Starrett, Miller Falls, and others were cranking

this thing out in

greater numbers than Stanley ever did, and examples by

manufacturers other than

Stanley are not valuable other than for use.

#289 Filletster and rabbet plane, 8 1/2"L, 1 3/4"W (1 7/8"W, 1936 on), 3 3/4lbs, 1911-1948. *

This is one of Stanley's

nicest planes, in my not so humble opinion. It's sort of a

hybrid between the #78 and the #278. It looks more

like the common #78, except with the noticeable

difference in the

cutter's width and that the cutter is skewed. There are

also the two scoring

spurs, and a depth stop and fence that can be positioned

on either side of the

plane, like the #278's capability. The lever cap's screw, the depth

stop's thumb screw, and

the fence's thumb screw are the only parts that are nickel

plated on this tool.

The sides of the plane are machined flat so that it can be

used on its side.

This is one of Stanley's

nicest planes, in my not so humble opinion. It's sort of a

hybrid between the #78 and the #278. It looks more

like the common #78, except with the noticeable

difference in the

cutter's width and that the cutter is skewed. There are

also the two scoring

spurs, and a depth stop and fence that can be positioned

on either side of the

plane, like the #278's capability. The lever cap's screw, the depth

stop's thumb screw, and

the fence's thumb screw are the only parts that are nickel

plated on this tool.

The sides of the plane are machined flat so that it can be

used on its side.

This plane can also be found with an improper fence.

A proper fence has

web-like additions to the casting (for strength) where the

portion for the rod

meets the fence proper; the rod slips through the fence's

opening for it

roughly about mid-way along the fence's length. An

inordinate number of these

planes turn up fitted with fences from a #78. It seems odd that so many of

them would have lost

their fences over time. Perhaps Stanley ran out of #289 fences and sold #78 fences as

replacements for those guys who either lost or broke the

original fence. It's

hard to say for sure, but one thing is certain - the #78 fence is

not designed to work well on this tool when the plane is

configured for left-handed

planing. The fence has two holes, one front and one back,

so that an auxilary

wooden fence can be added to the plane.

One thing to check on

this plane is that the arm unscrews easily and fits onto the

right side of the

plane. The arm has a hole drilled through its end so that a

nail can be

inserted through the hole to tighten the arm. The arm's

diameter of this plane

is larger than that of the #78's; the rod fills the hole in

its original fence, so

if you see a noticeable gap around the arm and the fence's

casting it's a good

bet that the rod isn't original. This isn't fatal to the

plane's function, but

if you're a collector you might experience a brain spasm

over it.

One thing to check on

this plane is that the arm unscrews easily and fits onto the

right side of the

plane. The arm has a hole drilled through its end so that a

nail can be

inserted through the hole to tighten the arm. The arm's

diameter of this plane

is larger than that of the #78's; the rod fills the hole in

its original fence, so

if you see a noticeable gap around the arm and the fence's

casting it's a good

bet that the rod isn't original. This isn't fatal to the

plane's function, but

if you're a collector you might experience a brain spasm

over it.

Also check that the spurs are ok, since the spurs

supplied with this plane

are unique to it (actually, the earlier models of the #10 1/4 use

the same spur, but these planes are far too expensive to

be used as a source

for replacement spurs). Each spur fits into a milled

recess, one on the left

and one on the right, and they are not interchangeable

with each other. Many of

the spurs are filed short so that they no longer can

protrude below the sole of

the plane. For a very brief time, Stanley made some of the

planes with the

three-lobed spurs that are identical to those used on the

#78 and

similar planes; this is the model to find, if you can.

The lever cap, along

the

righthand edge can sometimes be found with a large chip out

of it. You should

also make sure that the lever cap is really a proper one for

the plane, and not

one that was lifted from a #78 (or similar plane) as a

replacement. A proper #289 lever cap has an S-shaped

reinforcement ridge along

its right edge (relative to its position in the plane).

The lever cap also has

the unusual feature in that it must be pulled upward so

that the lever cap

fulcrum screw can engage the cap. Nearly all the other

planes that use a

similar lever cap slip down over the lever cap fulcrum

screw, taking efficient

use of gravity. Perhaps the designer of the #289's lever cap was from the

southern hemisphere, the

moon, or some place like that.

The lever cap, along

the

righthand edge can sometimes be found with a large chip out

of it. You should

also make sure that the lever cap is really a proper one for

the plane, and not

one that was lifted from a #78 (or similar plane) as a

replacement. A proper #289 lever cap has an S-shaped

reinforcement ridge along

its right edge (relative to its position in the plane).

The lever cap also has

the unusual feature in that it must be pulled upward so

that the lever cap

fulcrum screw can engage the cap. Nearly all the other

planes that use a

similar lever cap slip down over the lever cap fulcrum

screw, taking efficient

use of gravity. Perhaps the designer of the #289's lever cap was from the

southern hemisphere, the

moon, or some place like that.

The earliest models of the plane have the patent date

embossed in the area

just behind the cutter's bed. While you're looking for that

date, to see if you

have an early one, be sure to check the area of the casting

that spans between

the handle and body proper as it can sometimes crack.

#292 Scraper, 12 1/2"L, 2 1/2"W, 1 1/2lbs, 1933-1964.

More filler for this rag. A cheap scraper used on floors, for removing paint, etc. It did come with a leather pad, under the blade, to eliminate chatter, if that's important to you.

#340 Furring plane, 10"L, 2"W, 2 1/2lbs, 1905-1917. *

Yup, a plane designed to

remove fur, and a favorite among the PETA rank and file. Not

from animals, you

chucklehead, but from wood, as it came off the saw mill. How

would you like

that job, planing wood as it came off the saw? Too bad

What's My Line is off

the air. I woulda loved to hear Kitty Carlisle or Nipsey

Russell try to crack a

fur planer's rough exterior when giving him the third

degree.

Yup, a plane designed to

remove fur, and a favorite among the PETA rank and file. Not

from animals, you

chucklehead, but from wood, as it came off the saw mill. How

would you like

that job, planing wood as it came off the saw? Too bad

What's My Line is off

the air. I woulda loved to hear Kitty Carlisle or Nipsey

Russell try to crack a

fur planer's rough exterior when giving him the third

degree.

Judging by the length of time that this plane was

offered, you can tell that

fur planing was a popular pastime. Now, what is fur, in the

lumber sense? It's

the rough, fuzzy surface left from the sawing. Oftentimes,

the lumber was

chucked onto the ground before it was stickered. So, it was

like a dirt magnet.

Thus, some genius at Stanley, Rule and Level, Co. thought a

plane necessary to

tidy up the stock before a regular bench plane could be put

to the 'sullied' surface.

But that's the same function as the #40 and the #40

1/2. Or one

woulda thought so.

This plane is bizzare looking. When viewed from its

side, the plane's sole

makes contact only at its mouth and heel; between these two

points, the sole

arches upward. The toe is above the surface from just

forward of the cutter to

the toe's end. This wierd sole configuration, designed

purposely to minimize

the amount of contact with the wood, makes sworn members of

the Flat Plane

Society recoil in horror. If you ever stumble across one of

these planes, don't

bother trying to lap it, ok?

Looking at the plane

from the top, the plane swells around the cutter's position,

and tapers both

toward the toe and heel so that the plane is lighter in

weight. It certainly is

a unique looking chunk of metal. The entire bottom casting

is japanned, save

for the flat sections of the sole below the tote and around

the mouth. The

plane's model number is embossed right behind the knob.

Looking at the plane

from the top, the plane swells around the cutter's position,

and tapers both

toward the toe and heel so that the plane is lighter in

weight. It certainly is

a unique looking chunk of metal. The entire bottom casting

is japanned, save

for the flat sections of the sole below the tote and around

the mouth. The

plane's model number is embossed right behind the knob.

The knob and tote are beech, and each is held to the

main casting with a

one-piece steel screw, and not the two-piece brass nut and

bolt that's used on

the common bench planes. The knob has a unique shape to it,

where it tapers in

diameter where it sits atop the casting. Stanley must have

thought that this

shape would lessen the knob's chances to split about the

base, but many of the

planes show splitting there. The same general shape to the

knob can be found on

the early #40 and #40

1/2 scrub

planes.

A single, thick cutter is used, and is held in place

by a simple cap and

screw. The cutter rests on a simple fin-like projection that

arises out of the

main casting. The first model of the plane has "PAT APLd

FOR" stamped

into the iron just below the Stanley logo. Since there is no

mechanical

adjustment means for the iron, the backside of the iron is

smooth. Any milling

in the backside of the iron means it's a replacement.

You only want to own one of these if you're a

collector. Many of them are

found in very tough shape since they did suffer hard work.

Finding the planes

in anywhere near new condition is very tough.

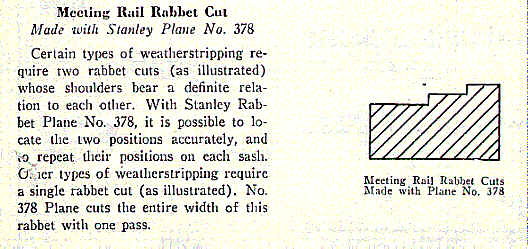

#378 Weatherstrip Rabbet plane, 8"L, 11/16"W (13/16"W, 1939 on), 2 5/8lbs, 1930-1958.

One woulda thought that

Stanley had exhausted every possible design for a plane to

make the cuts for

weatherstrip installation. But no, the New Britain think

tank was in overdrive,

and nothing could stop it from polluting the hardware

shelves of America with

more offal. First the #78, then the #278, and now the #378, with this one is designed

specifically to cut the

rabbets for metal weatherstripping on meeting rails of

sash and for general

rabbetting within its capacity. Wonder why there was never

a #178 -

maybe they had one on the drawing board, but it

frightened its designers to death and thus never got into

production?

One woulda thought that

Stanley had exhausted every possible design for a plane to

make the cuts for

weatherstrip installation. But no, the New Britain think

tank was in overdrive,

and nothing could stop it from polluting the hardware

shelves of America with

more offal. First the #78, then the #278, and now the #378, with this one is designed

specifically to cut the

rabbets for metal weatherstripping on meeting rails of

sash and for general

rabbetting within its capacity. Wonder why there was never

a #178 -

maybe they had one on the drawing board, but it

frightened its designers to death and thus never got into

production?

This one looks like the common #190 rabbet plane, loaded with some

factory options -

there are three depth stops (one on each side that can be

set at different

depths) and a fence that is roughly one-third the length

of the plane. The

fence is carried by two arms each of which screws into the

main casting. Check

that the casting isn't damaged where the arms screw into

the plane.

An extra wide depth stop, positioned on either the

left or right side of the

plane, was provided for use on the wider cutters, which were

optional with the

tool. A thumb screw, just like the one used to secure the

slitting cutter on

the #45,

is used to secure the depth stop in place. The plane came

equipped with an

11/16" cutter, which was then upped to 13/16" from 1939

on. Optional

cutters could be purchased: 11/16", 3/4", 7/8", and 1".

Two brass stop collars

are included so that pre-set positions of the rabbets can be

repeated from sash

to sash; the fence slams against these collars to maintain

the fence's

settings. These stop collars each have a small slotted screw

through them so

that the collars can be secured to the rear arm; the collars

are positioned so

that they 'sandwich' the fence. There is also a small cotter

pin that fits through

the rear arm. I have no idea what this pin does, other than

to make it

impossible for the fence to be removed from the arm - this

must be one of the

deep, dark secrets of weatherstripping that only a senior

member of WUA

(Weatherstripping Union of America) could answer. The astute

reader may quickly

realize that there are a lot of parts to this plane, and

they are usually MIA.

Two brass stop collars

are included so that pre-set positions of the rabbets can be

repeated from sash

to sash; the fence slams against these collars to maintain

the fence's

settings. These stop collars each have a small slotted screw

through them so

that the collars can be secured to the rear arm; the collars

are positioned so

that they 'sandwich' the fence. There is also a small cotter

pin that fits through

the rear arm. I have no idea what this pin does, other than

to make it

impossible for the fence to be removed from the arm - this

must be one of the

deep, dark secrets of weatherstripping that only a senior

member of WUA

(Weatherstripping Union of America) could answer. The astute

reader may quickly

realize that there are a lot of parts to this plane, and

they are usually MIA.

The plane is japanned with its sides machined flat.

The cutter is secured with

a nickel plated lever cap which is secured to the main

casting with a slotted

screw. The thumb screws to secure the fence and depth stops

are also nickel

plated. The fence has two holes drilled through it - one

near the front and the

other at the rear - so that a wooden face can be secured to

the fence. The

model number is embossed on the left side of the main

casting, just forward of

the handle.

In one of Stanley's pieces of tool propagada - one

devoted to tools for

weatherstrip work - they indicate that this plane is "Used

to make the

rabbet cuts on the sash meeting rail and for all rabbet work

within its

capacity." If you don't know what the sash meeting rail is,

it's the two

rails that align with each other, on double-hung windows,

when the window is

closed.

You don't want this plane for working. Save it for

the collectors. Trust me

here.

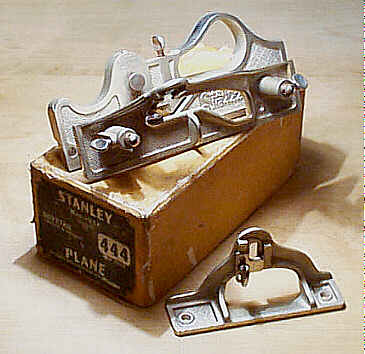

#444 Dovetail plane, 9"L, various widths, 6lbs, 1912-1938. *

Runner-up to the Mr.

Stupid Plane Pageant (in the event that Mr. Stupid Plane can

no longer remain

in that role, the runner-up shall assume the position and do

guest appearances

either on a televised workshop program decorated in plaid or

Vegematic

infomercials). This is a plane that only a mother or Rube

Goldberg could love.

Runner-up to the Mr.

Stupid Plane Pageant (in the event that Mr. Stupid Plane can

no longer remain

in that role, the runner-up shall assume the position and do

guest appearances

either on a televised workshop program decorated in plaid or

Vegematic

infomercials). This is a plane that only a mother or Rube

Goldberg could love.

First, it's the most difficult plane to grip, if you

have large neanderthal

paws. A hollowed and looped opening in the casting is fit in

the palm, with

your fingers wrapping around it. The cutter sticks way up

into the opening

where it's perfectly positioned to rip apart the knuckles of

a careless

dovetailer. The toe, where you place your left hand, has a

little bump in the

casting, which is supposed to be sufficient for grasping.

Hah! I defy you to

use this plane without drawing puss or blood!

There are three main cast iron parts to the tool: 1)

the main casting, which

carries the cutter; 2) the fence, which makes the plane work

perpendicularly to

cut the dovetail in one position and also makes the plane

work at an angle to

cut the socket in another position; and 3) a depth stop,

which controls how

deep the shoulder of the dovetail is cut. The main casting

has two sets of

tapped holes in which the 2 1/2" arms are screwed. The main

casting also

has the patent information "PAT'S / 6-28 / 8-23 / 1910"

embossed on

the right side. Both the fence and the depth stop each have

two countersunk

holes drilled through them so that a wooden face may be

secured. The fence and

the depth stop each also carry two pressed steel stops that

are positioned to

one of the tick marks of the scales that are stamped into

each casting. These

scales help to set-up the plane correctly in order to get

the consistancy

needed to cut the corresponding dovetail and groove. The

steel stops butt up

against a blued 'bolt' that's positioned on the left side of

the main casting,

just above the cutter.

The plane cuts a flared (20 degrees) tongue and

groove, which most of us

recognize as a sliding dovetail. The plane's working range

is a groove no more

than 3/4" deep and dovetail necks no narrower than 1/4".

It's a very

difficult plane to describe how it's used in words, but I'll

take a stab at it.

The sole of the plane is beveled at 20 degrees. A fence is

provided that can be

attached to the plane on either side, to give different

results, depending upon

which side the fence is placed. In one case, the fence is

attached to the right

of the plane's main casting, making it work perpendicularly

to the edge (the

plane is cutting the tongue portion), and in the other, the

fence is attached

to the left of the plane's main casting to tilt it 20

degrees (the fence has

two faces, which oppose each other at 20 degrees) to cut the

groove. In the

latter case, the fence is used only to pitch the plane and a

batten must be

used, like a common dado plane, to guide it. When the plane

is used to cut the

tongue, a depth stop is fixed to the left side of the main

casting. When the

plane is used to cut the groove, the angled fence doubles as

a depth stop. The

grooves are the toughest to cut using this plane.

The cutter is seated

at

a skew in the plane to facilitate cutting across the grain.

There are four

provided: 7/32", 3/8", 1/2", and 7/8". The cutter is

secured to the main casting via a plunger-like rod that's

activated by the

large thumb screw just forward of the grip. There are two

cast iron spur blocks

that are used to score the grain when working across the

grain; one spur block,

measuring 3/16" across the beveled face, is designed for the

narrow

cutters, and the other, measuring 5/16" across the beveled

face, for the

wider cutters. These spur blocks are secured to the right

side of the main

casting with two countersunk screws, just ahead of the

cutter. Another spur is

secured to the left side of the main casting. Since these

planes received very

little use, the spurs normally have plenty of length to

them, however, if you

find yourself in need of one, you can snarf them from the #289 or #10 1/4, both of which aren't low-cost

planes. Many of the

planes are missing cutters and one of the spur blocks.

The cutter is seated

at

a skew in the plane to facilitate cutting across the grain.

There are four

provided: 7/32", 3/8", 1/2", and 7/8". The cutter is

secured to the main casting via a plunger-like rod that's

activated by the

large thumb screw just forward of the grip. There are two

cast iron spur blocks

that are used to score the grain when working across the

grain; one spur block,

measuring 3/16" across the beveled face, is designed for the

narrow

cutters, and the other, measuring 5/16" across the beveled

face, for the

wider cutters. These spur blocks are secured to the right

side of the main

casting with two countersunk screws, just ahead of the

cutter. Another spur is

secured to the left side of the main casting. Since these

planes received very

little use, the spurs normally have plenty of length to

them, however, if you

find yourself in need of one, you can snarf them from the #289 or #10 1/4, both of which aren't low-cost

planes. Many of the

planes are missing cutters and one of the spur blocks.

The plane is entirely nickel plated, but even with

that, you'd still have to

be mighty desperate to own one of these (for use). Judging

by the number of

examples out there, most of which are in a remarkable state

of preservation,

with many in their original box, despair musta been oozing

from each and every

workshop that had this ghastly beast counted in its tool

arsenal.

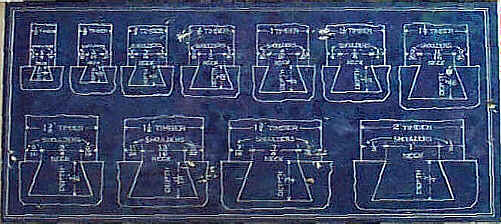

The earlier planes came in a finger-jointed wooden

box with a sliding top

while the later ones came in a cardboard box. Both boxes

have a bright blue

label, which shows the various dimensions of dovetails,

affixed to the

underside of the lid. A wooden box was provided to carry the

four cutters. The

box also has a diagonal line scribed across one face to

serve as a reference

for the proper grinding angle of the cutters. A sample

dovetail was also

commonly provided with the plane almost as if Stanley were

trying to prove to

the tool buying public that the plane actually works. We'll

never really know

for certain whether some unfortunate soul was chained to a

post in some New

Britain sweatshop, forced to use the plane all day long to

make the samples, or

whether a machine cut them and Stanley was pulling the wool

over Joe

Carpenter's eyes.

Stanley, in their catalogs, stated the plane could do

the following work

(tongue refers to the dovetail proper, while groove refers

to the socket):

- Dovetail tongue and groove joint with the groove cut in the regular manner, and the tongue cut on a bevel, used for supports.

- Dovetail tongue and groove joint with unequal shoulders, or a joint with a regular groove, but where the tongue is offset.

- Dovetail tongue and groove joint as can very often be conveniently used when one is forming and end to end timber match (like a scarf joint).

- Dovetail tongue and groove half joint, frequently used by carpenters to a very great advantage in concealed nail work.

- Dovetail tongue and groove joint where both the groove and tongue are cut on a beveled surface, making a strong corner.

- Dovetail tongue and groove joint for bracket support, where the bracket is dovetailed into the shelf.

- Dovetail tongue and groove joint as applied to the setting of gear teeth around the outer rim of any gear pattern.

[ START ] |

[ PREV ] | [ NEXT

] | [ END ]

[ HOME

]

Copyright

(c) 1998-2012 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved.

No part may be

reproduced by any means without the express written

permission of the author.