The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #71 - #87

Quick Find: #71, #71 1/2, #72, #72 1/2, #74, #75, #78, #78W, #A78, #79, #80 (rabbet), #80, #80M, #81, #82, #83, #85, #87

#71 Router plane, 7 1/2"L (7 5/8", 1962 on), various widths, 2 5/8lbs, 1885-1973.

And here you thought

routers are the stuff of the modern workshop. Nope! They've

been around much

longer than the abNORMal kind has, but these kind ain't the

'lectrical kind.

These kind are pushed or pulled, and are suited for

smoothing the bottom of a

groove, mortice, or whatever, which is lower than the

general surface of the

piece being worked. They were very popular tools, especially

with patternmakers

and stairbuilders. Every shop should have one. Stanley's

minister of propaganda,

in a leaflet distributed with the tool, stated:

And here you thought

routers are the stuff of the modern workshop. Nope! They've

been around much

longer than the abNORMal kind has, but these kind ain't the

'lectrical kind.

These kind are pushed or pulled, and are suited for

smoothing the bottom of a

groove, mortice, or whatever, which is lower than the

general surface of the

piece being worked. They were very popular tools, especially

with patternmakers

and stairbuilders. Every shop should have one. Stanley's

minister of propaganda,

in a leaflet distributed with the tool, stated:

"For surfacing the bottom of grooves or other

depressions parallel

to the surface of the work. There are many applications in

pattern making

cabinet work and in fact almost all kinds of woodworking

that call for these

tools. They are particularly practical for routing dadoes

for shelves, stair

stringers or where pieces of hardware are to be recessed

into the surface or

edge of a board, such as large hinges or lock strikes,

etc. It is not possible to

show all these, but the user will soon discover places

where these tools will

prove their value."

They are sorta D-shaped, with two turned hardwood

knobs (beech or maple) on

each end. The knobs flank an adjustable L-shaped cutter,

which protrudes

through a large, circular opening in the plane's sole. A

grooved post receives

the cutter, which is locked into position by a thumb screw

activated clamping

collar. This collar, as well as the cutters, are very easy

to lose, and these

planes are often found minus them. The grooved post is also

grooved on its

backside so that the cutter can be reversed, making the

plane function in a

bull nose fashion.

Originally, it came with only two cutters - 1/4"W and

1/2"W. These

two cutters are ground to a straight edge, so that they

operate just like a

paring chisel. They weren't well suited for smoothing, due

to tearout, so a

third, patented cutter was added in 1917. This one is

V-shaped.to make it

function like a plough (the farmer's kind) as it cuts the

wood. The earliest

version of this cutter is a one-piece construction, and can

sometimes be found

with the patent date stamped in its shank. Because the V

cutter has two bevels

on it, it proved difficult to grind and hone. Subsequently,

the cutter became a

two-piece design so that the end be removed for sharpening.

Late production

models of this plane have all three of their cutters

graduated in 1/16ths along

their shanks for fine adjusting.

The plane underwent many modifications during its

production by Stanley. The

first of which was arching the portion of the sole, forward

of the cutter, into

an open throat configuration. This was done ca. 1890. Then,

probably during the

mid-1890's, a mechanism to close the throat's opening was

added so that the

plane could work narrow surfaces, like grooving the edge of

a board, to add

lateral stability to the tool. This mechanism, or 'shoe' as

Stanley called it,

attaches to the round depth gauge rod that slips through the

arched area of the

main casting and 'closes' the throat to give more of a

bearing surface, or

sole, on the tool. It took Stanley a few designs to get this

right as the first

design of the shoe has a separate cutter collar casting that

projects forward

to carry the shoe and the depth gauge rod. Stanley soon

redesigned this to the

simpler method most are familir with today; the newer design

was less costly to

manufacture and much easier to use. The shoe's use is very

limited for most

work, but functions best as a depth stop, which is explained

next.

At the same time the

shoe

was added, a round depth gauge rod was made part of the shoe

clamping assembly.

This rod controls the tool's depth of cut as the cutter is

adjusted deeper. It

permits consistency from cut to cut, which would be

difficult to achieve were

the rod not provided. The rod has a smaller diameter portion

on one end. The

use of the stop might not be intuitive to most, but it's

very easy to use and

rather clever in its simple operation. The rod is slipped

through the round

opening for it, atop the arched portion of the main casting,

so that the

smaller diameter is downward. The tshoe is then slipped onto

the rod (over the

large diameter) so that the shoe is above the arched portion

of the main

casting. The rod is then positioned to the desired depth

(relative to the sole

of the main casting) and the screw of the shoe is tightened

onto the rod. The

rod is left free to move up/down through the arched portion

of the main casting

- do not tighten the screw to lock it in place. As the cuts

are made, the rod

will slip down toward the casting until the shoe stops it

from moving downward

anymore. Once the shoe makes contact with the arched portion

of the main

casting, the desired depth has been reached. Pretty simple,

eh?

At the same time the

shoe

was added, a round depth gauge rod was made part of the shoe

clamping assembly.

This rod controls the tool's depth of cut as the cutter is

adjusted deeper. It

permits consistency from cut to cut, which would be

difficult to achieve were

the rod not provided. The rod has a smaller diameter portion

on one end. The

use of the stop might not be intuitive to most, but it's

very easy to use and

rather clever in its simple operation. The rod is slipped

through the round

opening for it, atop the arched portion of the main casting,

so that the

smaller diameter is downward. The tshoe is then slipped onto

the rod (over the

large diameter) so that the shoe is above the arched portion

of the main

casting. The rod is then positioned to the desired depth

(relative to the sole

of the main casting) and the screw of the shoe is tightened

onto the rod. The

rod is left free to move up/down through the arched portion

of the main casting

- do not tighten the screw to lock it in place. As the cuts

are made, the rod

will slip down toward the casting until the shoe stops it

from moving downward

anymore. Once the shoe makes contact with the arched portion

of the main

casting, the desired depth has been reached. Pretty simple,

eh?

Next, in 1902, a vernier cutter adjustment mechanism

was added to the

grooved post; the cutters were redesigned to have a notch at

their top to

engage a wheel, which traverses a threaded rod to regulate

the cutter's depth.

This vernier adjustment made it possible to make fine

advances in the cutter's

set than is normally made when done manually. The feature

makes it possible to

advance the cutter in successive fine increments as the

recess is cut deeper

and deeper; i.e., instead of hacking out the recess with

just a few settings of

the iron, you rout the area with the cutter in a fine set,

loosen the blade

clamping collar, turn the vernier wheel a bit, clamp the

cutter firmly, then

rout the area. This procedure is repeated over and over

until the desired depth

is reached.

In 1909, countersunk (from above) screw holes,

through the sole, were added

to allow wood bottoms or fences to be attached. This allows

the tools to work

recesses that are larger than the tool is wide. In other

words, the tool can be

made physically 'larger' by attaching a wooden sole to it.

In the same year, 1909, the shoe to close the throat

was redesigned and

repositioned so that it became part of the arched portion of

the main casting.

During this redesign, the depth gauge rod was repositioned,

and in fact, the

shoe attaches directly to the rod.

An adjustable fence,

which is screwed to the sole, was added in 1939. It is

fastened to the

underside of the tool's sole by means of a single screw and

washer, both of

which are often missing. Two small screw holes that flank a

larger screw hole

(on either side of the cutter) indicate whether your version

originally came

equipped with the fence. The sole is also grooved to receive

the fence. The

fence is used for the times when the cutter is run parallel

to an edge. The

fence has a straight edge for straight work, and the other

side is curved to

allow the tool to follow either concave or convex edges.

An adjustable fence,

which is screwed to the sole, was added in 1939. It is

fastened to the

underside of the tool's sole by means of a single screw and

washer, both of

which are often missing. Two small screw holes that flank a

larger screw hole

(on either side of the cutter) indicate whether your version

originally came

equipped with the fence. The sole is also grooved to receive

the fence. The

fence is used for the times when the cutter is run parallel

to an edge. The

fence has a straight edge for straight work, and the other

side is curved to

allow the tool to follow either concave or convex edges.

As is the case with many Stanley planes, the first

models were japanned. The

earlier models have maple handles that are finished with a

clear varnish.

Toward the close of the last century, they became nickel

plated. This plane

follows that same course. The later models have hardwood

knobs that are painted

black, while even later models have composition or plastic

knobs. The plane is

still being made in England, but its quality pales in

comparison to the older

American versions.

You'll also see many of these planes cast in brass.

Stanley never made them

in this metal. The source of these brass planes is from the

many patternmakers

who made copies of ones they borrowed. It is an easy plane

to make, and with it

being particularly useful in the patternmaking trade, it was

inevitable that

enterprising patternmakers would 'roll their own' and save

themselves some

dinero.

#71 1/2 Router plane, 7 1/2"L, various widths, 2 1/8lbs, 1896-1949.

Good old Stanley, coming

up with a new model number to designate a plane that was

born after the

redesign of the #71.

This plane is nothing but the first model version of the #71! It has a closed

throat; i.e., there is no arching of the sole forward of

the cutter. It did

follow the same evolution of features, except for the

throat adjusting

mechanism, as found on the #71. It was a less expensive

version of the #71.

Good old Stanley, coming

up with a new model number to designate a plane that was

born after the

redesign of the #71.

This plane is nothing but the first model version of the #71! It has a closed

throat; i.e., there is no arching of the sole forward of

the cutter. It did

follow the same evolution of features, except for the

throat adjusting

mechanism, as found on the #71. It was a less expensive

version of the #71.

One might wonder why Stanley chose to manufacture the

two different models

of the routers, which only differ in the portion of the sole

ahead of the

cutter. Stanley claimed that the open throat of the #71 allows for easier passage of

the shaving, and that

it's easier for the worker to view the cutter's edge as

the tool is being

worked. However, there are some applications where the

open throat design

proved difficult to use, such as grooving a narrow piece

of work, in which case

the more sole that makes contact with the wood, the easier

it is to control the

tool's lateral stability. The #71 was hyped to be more versatile

and user friendly,

but at a greater cost than the simpler #71 1/2, which can do all that the #71 can. The image of

the two routers shows the differences in the throats; the

one on the left is an

earlier model of the #71 and has the open throat, while

the one on the right

is a #71 1/2 with its closed

throat.

There are fewer #71 1/2's out there

than there are of its non fractional sibling which should

clue the reader that

many guys didn't go for the closed throat design back

then. Even today, they

are tougher to sell to users, who prefer all the bells and

whistles that the #71 offers.

#72 Chamfer plane, 9"L, 1 5/8"W, 3 3/8lbs, 1886-1938. *

This plane is used to

chamfer the edges of stock, although it can't do stopped

chamfers all that

well. The plane has an inverted V-shaped sole, with each

"leg" of the

V serving as a guide while the plane is worked. Located

toward the front of the

plane is an inclined area onto which an adjustable sole

section is secured; the

mating surface between the main casting and the adjustable

sole is a broad

tongue and groove joint, with the adjustable sole part

carrying the tongue.

This plane is used to

chamfer the edges of stock, although it can't do stopped

chamfers all that

well. The plane has an inverted V-shaped sole, with each

"leg" of the

V serving as a guide while the plane is worked. Located

toward the front of the

plane is an inclined area onto which an adjustable sole

section is secured; the

mating surface between the main casting and the adjustable

sole is a broad

tongue and groove joint, with the adjustable sole part

carrying the tongue.

The adjustable portion of the sole carries the

cutter, and can be raised or

lowered to decrease or increase, respectively, the width of

the chamfer. With

the sole positioned in its lowermost position, the plane can

function as a

smoother. A brass five-spoked adjusting wheel (later

examples have a nickel

plated adjusting wheel) is used to secure the sole in the

desired position. It

can strip out from repeated hard use, so it's worth checking

that. A small

washer, usually long lost, fits below the spoked adjusting

wheel.

A typical rosewood

tote

and knob, like those found on the bench planes (the #3's are the exact size), are

used to push the plane.

The cutter is single (it has no cap iron). The plane's

original cutter is

sometimes lost, and replaced with one from a common block

plane. Remove the

lever cap and inspect the backside of the blade; an

original cutter will not

have a series of grooves, like those of a block plane,

machined into it. A

bullnose sole, which is usually long-lost, was added in

1909 to help the plane

cut stopped chamfers (you still have to work the stopped

areas by hand,

however, since there is an amount of sole ahead of the

iron). The image below

shows the plane with the bull nose section.

A typical rosewood

tote

and knob, like those found on the bench planes (the #3's are the exact size), are

used to push the plane.

The cutter is single (it has no cap iron). The plane's

original cutter is

sometimes lost, and replaced with one from a common block

plane. Remove the

lever cap and inspect the backside of the blade; an

original cutter will not

have a series of grooves, like those of a block plane,

machined into it. A

bullnose sole, which is usually long-lost, was added in

1909 to help the plane

cut stopped chamfers (you still have to work the stopped

areas by hand,

however, since there is an amount of sole ahead of the

iron). The image below

shows the plane with the bull nose section.

The planes do not use

a

cammed lever cap like those on the common bench planes.

Instead, the lever cap

is a japanned cast iron piece that is activated by thumb

screw. The earlier

models, such as that in the image, use the same japanned

thumb screw that's

common to specialty planes of the same vintage such as the #78. Later examples have the

nickel plated lever thumb

screws that have "STANLEY" embossed in them. The latest

models have

the nickel plated flat thumb screws with the fine knurling

about the

circumference.

The planes do not use

a

cammed lever cap like those on the common bench planes.

Instead, the lever cap

is a japanned cast iron piece that is activated by thumb

screw. The earlier

models, such as that in the image, use the same japanned

thumb screw that's

common to specialty planes of the same vintage such as the #78. Later examples have the

nickel plated lever thumb

screws that have "STANLEY" embossed in them. The latest

models have

the nickel plated flat thumb screws with the fine knurling

about the

circumference.

The earlier models will have a beaded knob and the

patent date cast into the

right side of the plane. The iron, which is bedded bevel

side down, can also be

found with the patent date, "PAT APR. 21, 85", stamped in

the iron

right below the Stanley name.

Curiously, many of the planes can be found with holes

drilled into the main

casting from both sides. Guys would fit a piece of wood or

metal into the V

portion of the sole so that the plane has a sole like a

common smoothing plane;

i.e., the wood or metal acts as a filler, with the holes in

the main casting to

permit screws to hold the filler in place. It might seem odd

that this filler

would be inserted into the sole, but it was done so that the

plane would cut

along the edge of stock. Were the plane not retrofitted with

this filler, only

the plane's toe would be the flat bearing surface of the

tool, which is far too

little an area when planing an edge, an edge normally

narrower than the width

of the plane's iron; i.e. were the filler not in place, the

heel would want to

bear on the edge, with the toe being raised off the edge.

#72 1/2 Chamfer plane, 9"L, various widths, 4 1/8lbs (total), 1887-1918. *

This plane is identical

to the #72, except

that it has an additional attachment for molding the

chamfers. The attachment

could be bought separately, but it seems that not too many

guys bought them as

they aren't that numerous. They are a real pain in the

arse to use, even though

they are supposed to function just like the #69 does.

This plane is identical

to the #72, except

that it has an additional attachment for molding the

chamfers. The attachment

could be bought separately, but it seems that not too many

guys bought them as

they aren't that numerous. They are a real pain in the

arse to use, even though

they are supposed to function just like the #69 does.

This attachment is secured to the plane like the

other soles are with the

spoked wheel that tightens it to the plane's main casting.

The attachment has a

two-piece cast iron construction, where the lower piece (the

one that carries

the cutter) slips under the upper piece (the one that

carries the spoked

wheel). The two pieces are held together with a screw that

has a knurled adjusting

'nut' midway along the screw. This screw allows the lower

section to be raised

or lowered relative to the upper piece so that the depth of

cut can be

regulated.

The cutters supplied with the attachment are

identical to those supplied

with the #69.

The cutters scrape a bead, reed, or flute on a flat

chamfer after that is cut

by the plane using one of the normal soles. The plane

itself is marked #72 but the beading

attachment has no markings, save for the patent dates that

are normally found

stamped into the blade securing nut. This nut, originally

brass and slotted,

was later made as a nickel plated thumb screw. The cutter

is held in place with

a staple like cast clamping piece. If this clamping piece

is broken or missing,

good luck trying to make it look original.

The plane is very seldom found with all its parts

(bull nose, regular sole,

and beading attachment). If you're a collector, buying just

the molding attachment

alone, with its cutters, can set you back a few bucks. The

earliest models have

polished brass on all but the two cast iron pieces, but the

later ones are

finished with nickel plating.

Check that the adjusting wheel isn't stripped. Also

check the lower piece

where the adjusting screw engages as it buttresses the

cutter's carrier. This

area is rather small and somewhat fragile and can crack.

#74 Floor plane, 10 1/2"L, 2 5/8"W, 10lbs, (21 1/2lbs 1909 on), 1886-1923. *

Don't think many of us

are gonna be using this one. It was designed to plane broad

wooden surfaces

such as bowling alleys, ship decks, floors, or whatever.

This is Stanley's only

plane that is used not on a bench in the standing position -

a long handle is

used to push the plane. It's also one of the most difficult

planes to find in

original condition; for example, it's far easier to find a #196 or #212 than it

is to find one of these in minty unmodified condition with

the original handle.

Don't think many of us

are gonna be using this one. It was designed to plane broad

wooden surfaces

such as bowling alleys, ship decks, floors, or whatever.

This is Stanley's only

plane that is used not on a bench in the standing position -

a long handle is

used to push the plane. It's also one of the most difficult

planes to find in

original condition; for example, it's far easier to find a #196 or #212 than it

is to find one of these in minty unmodified condition with

the original handle.

The plane has a 45" long turned (round) handle that

slips into a

pivotting hollowed receiver that's attached on the main

casting, below the

blade. The handle is maple or beech (I've seen a birch one,

too) and is tapered

from its overall diameter of 1 1/8" down where it joins the

receiver.

On the handle are two maple or beech totes. Each of

these totes sit atop a

nickeled casting to provide a flat base. The casting has a

hole through so that

a forging can pass through it; the lower end of the forging

is looped to slip

over the handle and the upper end is threaded to receive the

brass tote nut.

The brass tote nut is unique to this plane as it's oversized

from those used on

the common bench planes - it measures 5/8" diameter and is

13/16"

long.

The totes themselves are rather primitive looking

things (floor planing is a

rather oafish job afterall and there's really no need to

provide a Mercedes

when a Yugo will do) with a mostly 'vertical' profile. They

don't have

pronounced horns like those used on the bench planes. Some

users removed the

horns altogether so that they could butt the totes in the

palms of their hands

rather than wrap their hands around them.

The totes can be

positioned anywhere along the length of the handle and

anywhere around the

handle. The brass tote nut is loosened with a screwdriver,

which then allows

the handle to be rotated or moved along the handle. When

tightened, the brass

nut draws the looped end of the forging upward against the

wooden handle to secure

it in the desired position. Many of the brass nuts are

munged from use. Many of

the totes are also damaged, more often than not cracked,

from use. Some guys

shim the tote nut with washers in the tote's countersunk

cavity so that the

tote nut stands proud of the top of the tote.

The totes can be

positioned anywhere along the length of the handle and

anywhere around the

handle. The brass tote nut is loosened with a screwdriver,

which then allows

the handle to be rotated or moved along the handle. When

tightened, the brass

nut draws the looped end of the forging upward against the

wooden handle to secure

it in the desired position. Many of the brass nuts are

munged from use. Many of

the totes are also damaged, more often than not cracked,

from use. Some guys

shim the tote nut with washers in the tote's countersunk

cavity so that the

tote nut stands proud of the top of the tote.

Most of the planes are found without the handle. It's

a good bet that guys

found them better for staking tomatos than for floor

planing. Most of the

handles found on the planes are latter day reproductions. A

missing handle seriously

devalues the collectibility (and that's all the plane is

good for, right?) of

it - an original handle is worth more than the plane itself.

The main casting is just the #101 on tool sterrhoids, but with

the aforementioned

pivotting receiver. The receiver is secuted to the main

casting with a rod that

screw through the cheeks of the plane (the rod is slotted

on the left side).

Check that the receiver isn't damaged where it pivots

about the rod - it can

crack or break out there.

A double iron is used in this tool. The iron is the

same as that used on the

#8 sized

bench planes, but the cap iron is unique to the plane as

it isn't cut out to

accept an adjusting fork; the iron is adjusted manually.

If you need a cap

iron, good luck finding it as this is the only Stanley

plane that was equipped

with such a cap iron. In fact, the only part you can snarf

from this plane to

use on others is the iron. But, you'd be foolish to do

that, so don't.

The iron rests upon two sloping projections that

arise from the main

casting. These projections are milled so that they are

coplanar. The iron is

held in place with a simple lever cap; the lever cap is

oversized and has a

notch cast on its front so that it can slip under and engage

another rod

(screwed through the cheeks) when the lever cap screw is

turned. The lever cap

screw is nickel plated and has "STANLEY RULE & LEVEL

CO."

embossed around it much like that found on the #113. The earlier models of the

plane have the patent

date, "PAT. DEC.15-85.", embossed at the rear of the main

casting.

The plane is sometimes found modified. As mentioned

earlier, the totes are

reshaped. The plane can also be found with the sides of the

sole chamfered to

reduce the surface area in an attempt to cut down friction.

Sometimes wooden

soles are screwed to the main casting. The most common

modification is the

handle receive is drilled to accept a screw so that the

handle can be secured

to the plane. It seems Stanley forgot this important

feature. Some guys also

bend the heel of the iron upward to allow for a greater

range of movement on

the handle receiver.

Being 6' 3" tall, I can't find a position of the

totes to make for a

comfortable grip. One would likely be bent over somewhat to

use this thing and

I suspect workmen's compensation would go bankrupt if there

ever were a wave of

floor planing with this thing. Have pity on those old

hunchbacks you see

lurking around your local Acme Bowling Lanes for they

probably suffered these

planes during their youth. Lucky for us floor sandahs was

invented, hunh?

#75 Bull nose rabbet plane, 4"L (4 1/8", 1936 on), 1"W (1 1/16", 1936 on), 5/8lbs, 1879-1973.

This is a cheap, little

rabbet plane, that is very useful in the shop. It has a top

section that arches

forward of the blade to form the front portion of the sole.

This section is

adjustable, forward and backward, to regulate its mouth.

This is done by means

of a simple screw, which is threaded to lower section, the

rear portion of the

sole, of the plane. A washer sits under the screw, with the

earlier examples

having a brass washer. The plane does not have its number

cast into it. The

lower portion of the plane's sides is machined, with the

rest above the

machined area japanned.

This is a cheap, little

rabbet plane, that is very useful in the shop. It has a top

section that arches

forward of the blade to form the front portion of the sole.

This section is

adjustable, forward and backward, to regulate its mouth.

This is done by means

of a simple screw, which is threaded to lower section, the

rear portion of the

sole, of the plane. A washer sits under the screw, with the

earlier examples

having a brass washer. The plane does not have its number

cast into it. The

lower portion of the plane's sides is machined, with the

rest above the

machined area japanned.

The lever cap has a thumb screw to hold it and the

iron in place (earlier

examples will have a slotted screw). There are two lugs cast

into the top

section under which the lever cap fits. Sometimes the lever

cap is snapped and

repaired. The plane can choke easily since the lever cap

serves as the chip

breaker and it sits well back from the cutting edge. Despite

the tendency to

choke, the plane is useful for trimming and odd rabbeting. I

found it very

useful when cleaning up years of grunge and paint within the

window frames of

double hung sash.

The section of the sole ahead of the iron is not

co-planar with the sole

behind the iron. The plane is purposely made this way to

assist it with its cut

(you guys what owns the 'lectrical jointahs should know why

the plane's sole is

the way it is) so there's no need to practice sole lapping

on it.

#78 Duplex filletster and rabbet plane, 8 1/2"L (8 1/4", 1936 on), 1 1/2"W, 3lbs, 1885-1973.

This is another popular

Stanley plane, on which the company built a great fortune.

Nearly every workman

of the time had one of these planes in their kits. This

plane was so popular

and functional, that it still is made today. Any handtool

enthusiast should consider

this plane, or one like it, be it a competitor's or a wooden

version, as part

of his arsenal.

This is another popular

Stanley plane, on which the company built a great fortune.

Nearly every workman

of the time had one of these planes in their kits. This

plane was so popular

and functional, that it still is made today. Any handtool

enthusiast should consider

this plane, or one like it, be it a competitor's or a wooden

version, as part

of his arsenal.

The plane has two beds for the cutter - one

positioned for normal work, and

the other for bullnose work. The cutter has no cap iron, and

is held in place

by a thumb screw activated lever cap. Earlier models, with

the common floral

vines cast into the handle, required hand adjustment to set

the iron, but in

1925, a lever, which engages machined grooves in the

backside of the iron, was

provided to accomplish this. Around 1910, the handle has a

fish scale-like

pattern cast into it.

There is an adjustable depth stop on the right hand

side of the plane,

secured in place by a thumb screw. Directly below the depth

stop, is a

three-pronged spur to score the grain that sits flush with

the side of the

plane. It can be turned up out of the way when it isn't

needed. There is no

spur on the left of the plane.

A rod, threaded on one end, is used as the arm on

which the fence is

secured. The arm can be attached either to the left of the

plane, for working

right-handed, or to the right of the plane, for reversing

the plane to work

left-handed. This is a nice feature designed to handle

problem grain while

working. However, there is no provision for the depth stop

on the left side of

the plane, so you'll need to plane to a gauged line, or do

it by eye, when

using the plane left-handed. The threaded rod has a hole

drilled through it on

its end. This hole permits a nail, or something similar, to

pass through it in

order to tighten or loosen the rod. Many of the rods are

bent right where the

threads start so check this area by unscrewing the rod -

you'll notice whether

it's bent as you unscrew it.

The fence is secured to the arm with a thumb screw.

Sometimes you'll find

examples where the thumb screw is replaced with a slotted

round head screw.

This is due either to the thumb screw being misplaced, or

the original thumb

screw being stripped. Also, the fence is sometimes broken;

when the fence is

attached to the left side of the plane, the back portion of

the fence is longer

than the front portion by about 3/4". Look at the fence,

with the thumb

screw toward you. The aperture for the arm should noticeably

be to the left.

This plane is often found with parts missing - most

often it is the depth

stop and/or fence. You can usually scrounge parts from other

models, but this

approach usually ends up costing you more for an assembled

one than it does for

buying a complete one. It's also possible to find the plane

with the section of

the sole ahead of the bull nose bed snapped off. Some guys

ground this section

off so that they could use the plane as a chisel plane or to

worked stopped

rabbets right to their very end, which can't be done with

this portion of the

sole present. Planes that were accidently broken will have

the section brazed

back onto the main casting.

The #78 pictured with its original box

dates from the

1920's, with the most obvious clue being the depth

adjustment lever for the

cutter. It has the common decal on the handle, which

Stanley applied to many of

their planes and other handtools. It can be found applied

to the totes on the

Bailey and Bed Rock bench planes, special purpose planes

such as this one,

sliding bevels, try squares, etc. The block planes and

some of the other

smaller planes, like the #95, used a smaller decal that's

noticeably yellow (see

the #220 for an example of this decal).

The #78 pictured with its original box

dates from the

1920's, with the most obvious clue being the depth

adjustment lever for the

cutter. It has the common decal on the handle, which

Stanley applied to many of

their planes and other handtools. It can be found applied

to the totes on the

Bailey and Bed Rock bench planes, special purpose planes

such as this one,

sliding bevels, try squares, etc. The block planes and

some of the other

smaller planes, like the #95, used a smaller decal that's

noticeably yellow (see

the #220 for an example of this decal).

This #78 also illustrates another

common occurrence with Stanley - the use of early labels

on boxes of later

planes. The label on this plane, often called the "picture

label"

because of the line drawing of the tool contained within,

was in widespread use

starting around 1905. When this plane was made, Stanley

was in the midst of

what is known as the sweetheart era, where tools have the

heart logo stamped in

them somewhere. Even the box labels had a tiny heart on

them as part of the

logo. However, Stanley was also frugal in their

unwillingness to toss something

that was still perfectly usable, in this case a label. So,

here is a plane made

during the 1920's with a label used a few decades earlier.

Keep in mind that

it's impossible to date accurately Stanley stuff by the

boxes alone. Generally,

the latest feature on the tool, in this case the label, is

the more accurate

clue to the plane's approximate date of manufacture.

#78W Weatherstrip (Door) rabbet plane, 8 1/4"L, 1 1/2"W, 3lbs, 1936-1943. *

This is a very special

purpose plane, which none of us are likely to use. It is

designed for the

installation of weather stripping. The plane is like the

normal #78, except there is a

detachable steel runner on the sole of the plane. This

acts as a gauge for

cutting a 3/8" rabbet on either side of the plane, without

the need to

adjust the plane to do so. Stanley claimed that this

rabbet cut was

particularly useful for installing the weatherstripping on

the lock jamb and

the head of the door. Since the gauge is centered, the

plane can be worked left

or right handed (in other words, reversed) so that it

won't split out the grain

on the end of the door.

This is a very special

purpose plane, which none of us are likely to use. It is

designed for the

installation of weather stripping. The plane is like the

normal #78, except there is a

detachable steel runner on the sole of the plane. This

acts as a gauge for

cutting a 3/8" rabbet on either side of the plane, without

the need to

adjust the plane to do so. Stanley claimed that this

rabbet cut was

particularly useful for installing the weatherstripping on

the lock jamb and

the head of the door. Since the gauge is centered, the

plane can be worked left

or right handed (in other words, reversed) so that it

won't split out the grain

on the end of the door.

The plane does not have the number 78W cast into it,

and looks like any

regular #78,

especially since the runner is often missing on the plane.

The dead give-away

of this plane is a captive knurled locking nut or

pivotting steel locking lever

located right below the cutter adjustment. The nut or

lever locks the runner to

the sole of the plane.

The runner has two pins - one located toward the

front and the other toward

the back - which fit into holes that are drilled through the

plane's sole. At

about the mid-point of the runner is attached a projecting

boss, onto which the

the locking means is fixed above. There are several means by

which the runner

is locked in place. Some models carry a captive nut on the

main casting, and

engage threads on the boss. Others, like the two illustrated

here, have

pivoting levers that engage a groove machined on the boss.

Stanley did not originate this idea. Some unknown

firm retro-fitted #78's a decade or two

earlier, and then resold them. These models have a runner

with two long

pin-like projections that engage the plane. The runner

locking mechanism is a

bit different in that it is a pivoting piece of metal that

swings into place to

engage a hook-like projection on the runner. There is an

elongated slot milled

into the sole of the plane to accomodate the hook-like

piece of the runner.

#A78 Duplex filletster and rabbet plane, 8 1/4"L, 1 1/2"W, 1 1/4lbs, 1925-1934. *

Thankfully, the last of the aluminum abberations. Same as the #78, but cast in aluminum, including the fence, lever cap, and depth stop. If you're a collector, don't buy one that has iron anything on it.

Just imagine if this thing sold like no tomorrow

giving Stanley fits of

aluminum marketing opportunities. I'd probably be writing

about an aluminum

shootboard or something like that.

#79 Side rabbet plane, 5 1/2"L, 1/2"W, 5/8lbs, 1926-1973.

The #79 is a popular plane (heck, it's

one the few that is

still available new). The only knock against it that I

have is that the

trailing cutter's set ought to be backed off completely so

that it doesn't drag

behind the leading cutter, which is what is doing the

actual cutting. The #79 is also longer than the #98/#99 pair,

which may be a concern if you're working small areas. The

depth stop has two

screws that must be loosened/tightened when adjusting it.

Those are the only

real differences.

The #79 is a popular plane (heck, it's

one the few that is

still available new). The only knock against it that I

have is that the

trailing cutter's set ought to be backed off completely so

that it doesn't drag

behind the leading cutter, which is what is doing the

actual cutting. The #79 is also longer than the #98/#99 pair,

which may be a concern if you're working small areas. The

depth stop has two

screws that must be loosened/tightened when adjusting it.

Those are the only

real differences.

These are handy little goobers used to clean up

rabbets, dados, and grooves.

There are two opposing cutters locked in place with thumb

screws. The plane can

be used for left or right cuts. There are two nose pieces

which are reversible

to allow for bullnose work (the first image shows the plane

in its bull nose

configuration).

If anything bad can be said about this plane's use,

it has to be that its

cutters are too narrow. There are times when a rabbet is

larger than this plane

can handle. For these rabbets, the wooden plane versions of

the side rabbets

are ideally suited - they are capable of cleaning up rabbets

up to ~2"

wide or deep.

The earlier models

have a

semi-circular cutout on the top of the plane, between the

two cutters. Later

planes, starting ca. 1950, don't have this cutout, but do

have a hole in the

middle for hanging the plane on a hook. A depth stop, which

runs nearly the

full length of the plane, was also added about the same

time. The depth stop is

held in place by two small nickel plated thumb screws, but

the last production

American ones use slotted screws as do the current English

manufactured models.

The depth stop is made of stamped steel. You can find first

model examples that

are modified to accept a homemade depth stop.

The earlier models

have a

semi-circular cutout on the top of the plane, between the

two cutters. Later

planes, starting ca. 1950, don't have this cutout, but do

have a hole in the

middle for hanging the plane on a hook. A depth stop, which

runs nearly the

full length of the plane, was also added about the same

time. The depth stop is

held in place by two small nickel plated thumb screws, but

the last production

American ones use slotted screws as do the current English

manufactured models.

The depth stop is made of stamped steel. You can find first

model examples that

are modified to accept a homemade depth stop.

The cutters are secured with small cast iron clips,

which are held to the

main casting with small thumb screws. These thumb screws, as

well as the thumb

screws that are used to hold the depth stop, can strip out.

Be sure to check

these as it's a fairly common problem on this plane and the

#98 and #99. The

screws that hold the nose piece in place are countersunk

so that they don't

interfere with the plane's cutting action. These screws

are often seized in

place from the plane's sitting idle for so long.

Some common damage to be aware of for this plane, and

the #98 and #99 side

rabbets, is a stress crack that runs parallel to the

cutter. The crack is easy

to spot by examining the plane from its backside, the flat

side of the plane.

Look carefully about the top of the mouth to the side

where the bed meets the

mouth. The crack is usually the result of too much

pressure being applied by

the plane's blade clamping device, which is nothing but a

cast piece secured by

a thumb screw. On the models with the depth stop, you have

to remove it to

examine the areas for stress cracks.

Most of these planes are found fully nickel plated.

During WWII, the plane

was japanned. These models are fairly scarce.

#80 Steel cased rabbet plane, 9"L, 1 1/2"W, 1 5/8lbs, 1877-1888.

These are hybrid planes,

where wooden plane meets metal plane in a short-lived union.

In fact, these are

Stanley's only planes they ever offered that may remotely be

considered wooden

planes. Stanley may have made these planes as their answer

to the finer infill

planes that were all the rage in England. Of course, this is

pure speculation,

but it does seem strange that an iron plane slinging company

would take to

making a plane that sure has a goodly amount of wood as part

of it.

These are hybrid planes,

where wooden plane meets metal plane in a short-lived union.

In fact, these are

Stanley's only planes they ever offered that may remotely be

considered wooden

planes. Stanley may have made these planes as their answer

to the finer infill

planes that were all the rage in England. Of course, this is

pure speculation,

but it does seem strange that an iron plane slinging company

would take to

making a plane that sure has a goodly amount of wood as part

of it.

The plane is made up of a one piece U-shaped metal

sole, which is bent

upward to form the sides of the plane. Sandwiched inside

this chunk of metal

are two pieces of wood stuffing - one forward of the cutter,

and one behind the

cutter (as the bed). These pieces of wood are secured to the

metal with

countersunk screws. The wood stuffing has the patent date

stamped forward of

the cutter, and the company logo behind the cutter. The

plane is not marked

with the model number.

A long rod extends through the back piece of wood,

onto which a cast iron

japanned clamp is attached on the cutter side, with a brass

thumb screw (over a

brass washer) threaded on the heel. When the thumb screw is

turned, it pulls

the clamp up against the slotted cutter, increasing the

pressure on it to hold

the cutter in place. This method of securing the cutter is

nearly identical to

one of the first blade securing mechanisms ever patented in

this country - the

one by Thomas Worall, a former Baptist minster turned

planemaker. His patent of

1856, while working in Charlestown, Boston, and Lowell, MA,

had to be the

inspiration for the later Stanley design, and Stanley didn't

have to worry

about patent infringement as the Worall patent had expired

by the time Stanley

put this plane in production.

These planes are very

difficult to find in good condition. Makes a guy wonder

whether the planes were

used for rabbeting railroad ties, or something like that.

Most of the planes

have their mouths filed wider to open them up, probably

because many an

American woodworker of the day wouldn't appreciate a tight

mouth if it came up

and hit him on his, well, his mouth. Actually, the planes

have a major design

problem - they choke very easily with the mouth as Stanley

provided, and in

order for them to work well, the mouth had to be filed open

somewhat; the face

of the iron, along its edges, butts right against the steel

(see the #90 version of

this plane for an image of the other side of the plane,

where there is a very

slight relief to the steel ahead of the iron, but only for

a too short

distance). Thus, you're more likely to find the proverbial

needle in a haystack

before you find one of these planes that hasn't been on

the wrong end of a

file.

These planes are very

difficult to find in good condition. Makes a guy wonder

whether the planes were

used for rabbeting railroad ties, or something like that.

Most of the planes

have their mouths filed wider to open them up, probably

because many an

American woodworker of the day wouldn't appreciate a tight

mouth if it came up

and hit him on his, well, his mouth. Actually, the planes

have a major design

problem - they choke very easily with the mouth as Stanley

provided, and in

order for them to work well, the mouth had to be filed open

somewhat; the face

of the iron, along its edges, butts right against the steel

(see the #90 version of

this plane for an image of the other side of the plane,

where there is a very

slight relief to the steel ahead of the iron, but only for

a too short

distance). Thus, you're more likely to find the proverbial

needle in a haystack

before you find one of these planes that hasn't been on

the wrong end of a

file.

The plane was first offered without the iron skewed,

which is fine for

rabbeting with the grain, but Stanley soon realized that

most most wooden

rabbet planes have skewed irons to assist the plane when

working across the

grain, so they soon redesigned the plane to have a skewed

iron. The first model

also uses a captive lever cap and a round brass thumb screw

to secure the iron.

The lever cap pivots on a pin that is fastened to the steel

sides.

The clever reader might take notice that there are

two #80's offered

by Stanley. This plane, the wooden #90, and the

bull nose #11, are the only common Stanley

plane numbers that

were re-issued; there are two #80's

- this rabbet plane and the cabinet scraper (follows) -

and two #90's

- the other wooden rabbet plane - and two #11's - the beltmakers plane and

the bull nose

cabinetmaker's rabbet plane. The #80 and #90 planes were

never offered concurrently, so there was never any

confusion over which plane

was which, but the #11's were

offered concurrently, with the bull nose rabbet likely

only offered over in

England.

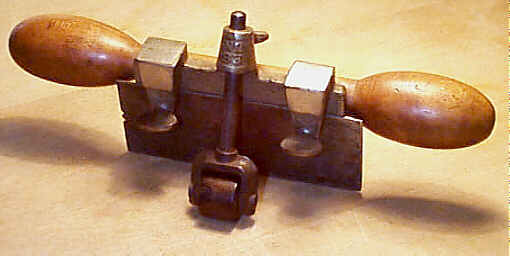

#80 Cabinet scraper, 11"L (11 1/2", 1947 on), 2 3/4"W, 1 3/4lbs, 1898-1984.

The common scraper that

many a cabinetmaker owned, if he didn't want to burn his

fingers. The middle

portion of the cast iron tool is semi-rectangular in shape

and has two handles,

sorta gullwing-like, which flank the 'rectangle'. The blade

is fit into a

milled 'bed' of the rectangular area and is secured in place

with a flat bar of

metal; the blade tilts toward the flat bar. The flat bar

puts pressure against

the blade by means of two thumb screws that thread into the

main casting; this

arrangement is what secures the blade to the tool, and a

nail pushed through

the holes in the thumb screws permits the blade to be

secured tightly. To the

rear of the blade, on the other side of the casting, is

another thumb screw,

which when turned puts some pressure on the blade from

behind causing the blade

to bow or spring. This action puts a slight curve on the

blade and is, in

essence, the blade's depth adjuster; turning the thumb screw

to the right

increases the blade's set, while turning it to the left

decreases it. The

handles each have a hole drilled in them so that it can be

hung out of the way.

The common scraper that

many a cabinetmaker owned, if he didn't want to burn his

fingers. The middle

portion of the cast iron tool is semi-rectangular in shape

and has two handles,

sorta gullwing-like, which flank the 'rectangle'. The blade

is fit into a

milled 'bed' of the rectangular area and is secured in place

with a flat bar of

metal; the blade tilts toward the flat bar. The flat bar

puts pressure against

the blade by means of two thumb screws that thread into the

main casting; this

arrangement is what secures the blade to the tool, and a

nail pushed through

the holes in the thumb screws permits the blade to be

secured tightly. To the

rear of the blade, on the other side of the casting, is

another thumb screw,

which when turned puts some pressure on the blade from

behind causing the blade

to bow or spring. This action puts a slight curve on the

blade and is, in

essence, the blade's depth adjuster; turning the thumb screw

to the right

increases the blade's set, while turning it to the left

decreases it. The

handles each have a hole drilled in them so that it can be

hung out of the way.

The blade is ground to a 45 degree bevel and has the

hook turned toward the

flat side of the blade. When the blade is inserted into the

tool (do this from

the sole so that you don't injure the burr), be sure that

the hook is oriented

so that it's toward the direction in which the blade leans.

The tool is pushed

with the blade leaning away from you. A solid grip and

moderate downward

pressure on the handles will have you scraping in no time.

Your fingers will

thank you daily when you use this common tool. The one knock

on the tool is

that it doesn't have the fine adjusting mechanism that the #12 family of

scrapers do and that the blade can't be pitched for

optimal performance on a

given wood like the #12 can.

The entire plane is japanned, but the thumb screws

and flat bar are nickel

plated. The tool's vintage can be determined by the logo

stamped on the flat

bar and on the cutter. The first model of the scraper has

the leading edge

(relative to the direction the tool is pushed) of the main

casting cast

straight across, whereas the later models have the same edge

cast convex. The

earliest model has the patent date embossed into the tool.

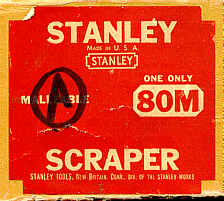

#80M Cabinet scraper, 11"L, 2 3/4"W, 1 3/4lbs, 1930-1974.

This is the malleable

iron version of the tool, probably aimed at the punks that

populated the trade

schools to keep the tool intact after they got done throwing

it at each other,

running it through the tablesaw, using it as a doorstop,

etc. The plane is

embossed "80M". This model isn't found as frequently as its

grey iron

brother, the #80,

but that doesn't make it valuable, except as a user or

maybe even as a

boomerang in the outback.

This is the malleable

iron version of the tool, probably aimed at the punks that

populated the trade

schools to keep the tool intact after they got done throwing

it at each other,

running it through the tablesaw, using it as a doorstop,

etc. The plane is

embossed "80M". This model isn't found as frequently as its

grey iron

brother, the #80,

but that doesn't make it valuable, except as a user or

maybe even as a

boomerang in the outback.

Curiously, Stanley chose to slap a red label on the

box for this tool

instead of the common green label that was in widespread use

when this plane

was manufactured. Red was the color used for the Bed Rock

line of bench planes.

Perhaps Stanley had some red ink left over, and rather than

using it on the

balance sheets they chose to use it for this plane's label

instead.

#81 Cabinet scraper, 10"L, 2 1/2"W, 2 1/4lbs, 1909-1942.

This is a nickel plated

and fancier version of the #80. It has a captive pivoting

lever cap that is

activated by a thumb screw to secure the blade into place.

The scraper has a

rosewood sole screwed to the bottom with four screws, one

each near the corners

of the sole. This was offered for the finest scraping,

where wood on wood is

thought to be preferable by some. The tool also has holes

drilled into the

handle to hang it out of the way while not in use. What it

doesn't have is a

fine adjustment mechanism for the blade, so you'll have to

have a light touch,

and be very familiar with the finer points of scraping,

before you tackle this

one. That is, if you intend to use it and not collect it.

This is a nickel plated

and fancier version of the #80. It has a captive pivoting

lever cap that is

activated by a thumb screw to secure the blade into place.

The scraper has a

rosewood sole screwed to the bottom with four screws, one

each near the corners

of the sole. This was offered for the finest scraping,

where wood on wood is

thought to be preferable by some. The tool also has holes

drilled into the

handle to hang it out of the way while not in use. What it

doesn't have is a

fine adjustment mechanism for the blade, so you'll have to

have a light touch,

and be very familiar with the finer points of scraping,

before you tackle this

one. That is, if you intend to use it and not collect it.

Like the #12 1/2, which also has a rosewood

sole screwed to the main

casting, this tool is often found with the sole shot from

years of use (hell,

even Stanley would sell you extra soles in anticipation of

the wear on them).

If you find one that has the screw points poking through

the sole, it's time

for a replacement, if you intend to use it. The reason why

is left as an

exercise for the reader. You can use whatever wood you

wish as a replacement

since finding a source of brazilian rosewood isn't easy

for most folks. The

sole's original thickness is around 1/4".

The blades used in the #12 family scrapers are not

interchangeable with this

tool - they are too wide for it. The blades used in the #80 are too short for

this tool. So, if you need a blade for it, you'll have to

search for it as the

blade to this one is a unique dimension. And all the

chuckleheads at Stanley

had to do was make the fool thing 1/2" wider to make for

scraper harmony.

The WWII version of this tool is japanned, and is

rather rare, but since no

one collects worlwartwotypes (said in as few syllables as

possible) no one

really cares about them. The handles have the rippled

texture to the casting,

like that of the #66 beader. The blade is prepared

like the the #12's.

#82 Scraper, 14 1/2"L (12 1/2", 1934 on (12", 1941 on)), 3"W, 1 3/4"lbs 1907-1958.

Another scraper, which

sorta looks like the #70 box scraper. It has a long,

turned wooden handle,

which has a pivoting portion to hold the scraper blade.

This pivoting portion

has a turned knob, which is gripped in the other hand, and

a clamping mechanism

to secure the blade. The advantage of a scraper of this

design is that the

blade can be adjustable to different angles, and the

workman could bear down on

it better than other designs.

Another scraper, which

sorta looks like the #70 box scraper. It has a long,

turned wooden handle,

which has a pivoting portion to hold the scraper blade.

This pivoting portion

has a turned knob, which is gripped in the other hand, and

a clamping mechanism

to secure the blade. The advantage of a scraper of this

design is that the

blade can be adjustable to different angles, and the

workman could bear down on

it better than other designs.

There are two designs of this tool. The first model

has the lever cap screw

on the face opposite the turned knob. This model uses a

simple thumb screw that

passes through a slotted arc-shaped piece to secure the

blade at one of four

angles (there are four notches cut into the slot of the

arc-shaped part).

During the early 1930's, the tool was redesigned to take

advantage of a new

patent that called for notches cut into two opposing mating

surfaces. These

notches don't allow the 'infinite' freedom of the blade's

position either since

the notches in the pivotting assembly slip into each other

in a predetermined

fashion. On the positive side, these notches offer greater

'holding' power and

won't slip under a heavy load like the previous design can.

The redesign also

called for a spring, located behind the front knob on the

opposite face, to cushion

the blade and eliminate chatter. To accomodate these two

changes, the turned

knob was moved to a position slight lower on the clamping

mechanism and the

lever cap screw was repositioned to the same face as the

turned knob.

Because of the way the blade is clamped in place, and

because the clamping

mechanism is unencumbered to either side, the tool is

capable of holding blades

of any width, making it useful for scraping into weird

locations that aren't

accessible by the other scrapers. Paint scraper blades, in

the shape of a broad

and flattened U were also provided for this piece later in

its production.

The handle and knob are maple, and on the earliest

examples they have a

clear finish on them. Starting in the early 1940's, the

finish became a deep

maroon. A ferrule is situated at the juncture of the handle

and where the cast

iron 'tang' is inserted into it. The cast iron portion of

the plane is

japanned, while the thumb screws are nickel plated.

#83 Wood scraper, 9 1/2"L, 3"W (4", 1914 on (3 7/8", 1925 on), 1 1/2lbs, 1897-1934.

This is one of those strange tools that makes you wonder who would ever design such a thing, let alone manufacture it. The obvious answer, in case you're in suspense, is Justus Traut and The Stanley Rule and Level Co.

It's basically a rectangular casting that accepts a

caster-like roller, and

has a turned wooden handle screwed onto it. The handle,

which is maple or beech

with a clear finish on it, is shaped like a dumbbell but

with sausage-shaped

ends that are gripped in each hand. Between the two

'sausages' is a cylindrical

portion through which a countersunk screw fits into the main

casting. The

handle can be removed to permit the scraper to work into odd

corners.

The main casting is

nickel plated, and has 3 thumb screws threaded into it.

There are two screws

that hold the blade in place; the blade slips into two

slit-like slots cut into

respective swellings of the main casting. These areas can

crack since they

carry much of the strain placed upon the tool during its

use; look about them

for any repairs or hairline cracks. The earliest examples

have the patent date

proudly embossed above the handle.

The main casting is

nickel plated, and has 3 thumb screws threaded into it.

There are two screws

that hold the blade in place; the blade slips into two

slit-like slots cut into

respective swellings of the main casting. These areas can

crack since they

carry much of the strain placed upon the tool during its

use; look about them

for any repairs or hairline cracks. The earliest examples

have the patent date

proudly embossed above the handle.

Between these two swellings is a conical portion of

the casting which rises

above the rest of the main casting. This conical portion has

a vertical hole

drilled through it and accepts a sliding post that in turn

terminates with a

roller. The sliding post is positioned within the conical

portion via a

thumbscrew. This area of the main casting also is

susceptible to damage since

it, too, carries a great amount of strain during use; a

close scrutiny about it

is wise.

The roller itself is maple or beech and it, along

with its captive post, is

usually missing in action. The wooden roller is sometimes

found cracked or with

missing chunks out of it. The roller came in two widths -

one measuring around

5/8" in length and the other about 1" in length. The post

that

carries the roller has a flat milled on it so that the

thumbscrew can lock it

in place better and so that the roller aligns properly

relative to the blade;

if the roller were allowed to be positioned so that its axis

isn't parallel to

the face of the blade, the tool would want to wander in a

direction you don't

want it to go.

So, what's the supposed appeal of this contraption?

The presence of the

roller eliminates the strain placed upon the wrists and

hands during the tool's

use. Also, the pitch of the blade can be customized simply

by sliding the post

up or down through the main casting; moving the roller

closer to the main casting

pitches the blade at a steeper angle. The roller can be

positioned so that the

scraper is oriented to make inoperable. The tool can be

pulled or pushed. You

want to make sure that the roller precedes the blade so it

doesn't leave any

track marks on the wood; i.e., the tool is oriented so that

the roller is away

from you.

Forget this dumb tool and get a real scraper, like a

#12 or #112,

instead. It does have a plus side, however - it's the

widest of all the

Stanley-made scrapers since it can accept a 4" wide blade,

but the blades

are normally long gone in these things. A #12 blade will not fit into

this tool; it's too wide

and too thick to slip into the slits cut for it in the

main casting. You need a

thinner iron to work in this tool.

#85 Cabinet maker's scraper plane, 8"L, 2"W, 2 5/8lbs, 1905-1934. *

This is a scraper plane

with a rabbet mouth and tilting knob and tote. It is

designed to work into

corners, where the knob and tote are tilted to prevent

smashing your knuckles,

an application that every woodworker does at least 3 times

daily.

This is a scraper plane

with a rabbet mouth and tilting knob and tote. It is

designed to work into

corners, where the knob and tote are tilted to prevent

smashing your knuckles,

an application that every woodworker does at least 3 times

daily.

The plane resembles a conventional bench rabbet, like

the #10 1/2, but

the frog design is totally different. It is a two piece

construction, where a

captive pivoting lever cap is pinned to another L-shaped

piece, which is in

turn screwed to the bottom casting much like the frog of

the common Bailey

bench plane is. The blade is secured into the frog using a

thumb screw, as

might be guessed, but it does so in a manner opposite what

is common on other

planes. The thumb screw is not on the pivoting lever cap

but is located behind

the cutter. As the thumb screw is tightened, it throws the

top of the cutter

forward toward the top of the lever cap, causing the lever

cap to pivot,

ultimately placing pressure at the bottom of the lever cap

over the width of

the cutter. The plane has the lever cap screw arranged

thus since there isn't

enough room to accomodate it freely due to the fact that

the frog leans toward

the knob; there isn't sufficient clearance between frog

and knob. Look for any

signs of repair or breakage where the lever cap is pinned

to the L-shaped

piece.

The frog can be adjusted forward or backward somewhat

to regulate the

opening of the mouth. This is done manually, by backing off

the pressure of the

two screws, which hold the frog to the bottom casting.

Between these two

screws, and a bit behind them, is another smaller set screw.

This screw can be

turned to adjust slightly the blade's pitch. If it is set

too much, and too

much presure is applied to the frog's other two screws,

cracking of the frog's

casting can occur about the set screw. Check this area very

carefully, if

you're to purchase one of these.

The tilting rosewood

knob

and tote are susceptible to cracks and breakage about their

bottoms. Both are

secured in place like the #10

1/4's

are. Look both the knob and tote over

carefully for any signs of damage, repair, or replacement.

You can't salvage

replacement knobs and totes from any old bench plane - you

have to snarf them

from a broken #85

or #10 1/4,

both of which aren't found under rocks in any part of our

great and wealthy

country.

The tilting rosewood

knob

and tote are susceptible to cracks and breakage about their

bottoms. Both are

secured in place like the #10

1/4's

are. Look both the knob and tote over

carefully for any signs of damage, repair, or replacement.

You can't salvage

replacement knobs and totes from any old bench plane - you

have to snarf them

from a broken #85

or #10 1/4,

both of which aren't found under rocks in any part of our

great and wealthy

country.

During use, the blade springs backward, which then

allows the shavings to

escape. The tool is pushed and gripped like a regular bench

plane. Despite all

its clever features, it wasn't very popular, and is now a

very collectible

tool. The blade is unique to this plane as its width

increases (over its

length) to fill the rabbet mouth. There isn't a lot of

useable meat on these

blades, and they are often long gone having been used up in

a day or two. The

most desireable planes will have the Stanley logo stamped on

the cutter, which

gives the collectors a warm and fuzzy feeling over its

originality.

#87 Cabinet maker's scraper plane, 8"L, 2"W, 2 1/2lbs, 1905-1917. *

This is a very rare plane, which never was popular due to the other cheaper and more versatile scrapers Stanley offered. This one is very much like the #85 in appearance, except that it doesn't have a rabbet mouth, nor does it have the tilting knob and tote. On this model, the knob and tote are secured to the bottom casting with a brass slotted screw and a threaded rod. Other than that, the plane is identical to the #85 in every regard, and suffers the same possibility of damage that that one does. The plane was practically DOA with the ballsy #112 doing the same duty, and much better at that, than this one does. The mind goes apoplectic when pondering why Stanley didn't offer a corrugated version of this one - wow, imagine what one would be worth if they had?

[ START ] |

[ PREV ] | [ NEXT

] | [ END ]

[ HOME

]

Copyright

(c) 1998-2012 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved.

No part may be

reproduced by any means without the express written

permission of the author.